By Frances Walsh | 27 Jan 2021

The Seagull is a small two-stroke, single-cylinder petrol outboard engine, manufactured in England between 1931 and 1996. Aficionados—there are many—point out that one features in The Talented Mr. Ripley, a film adaptation of a 1950s Patricia Highsmith novel. In a dinghy, Dickie Greenleaf (Jude Law) is throttled by the titular Mr Ripley (Matt Damon) with an oar as he starts up a Seagull. Disappointingly, the Seagull is not authentic to the period, the square tank being a giveaway.

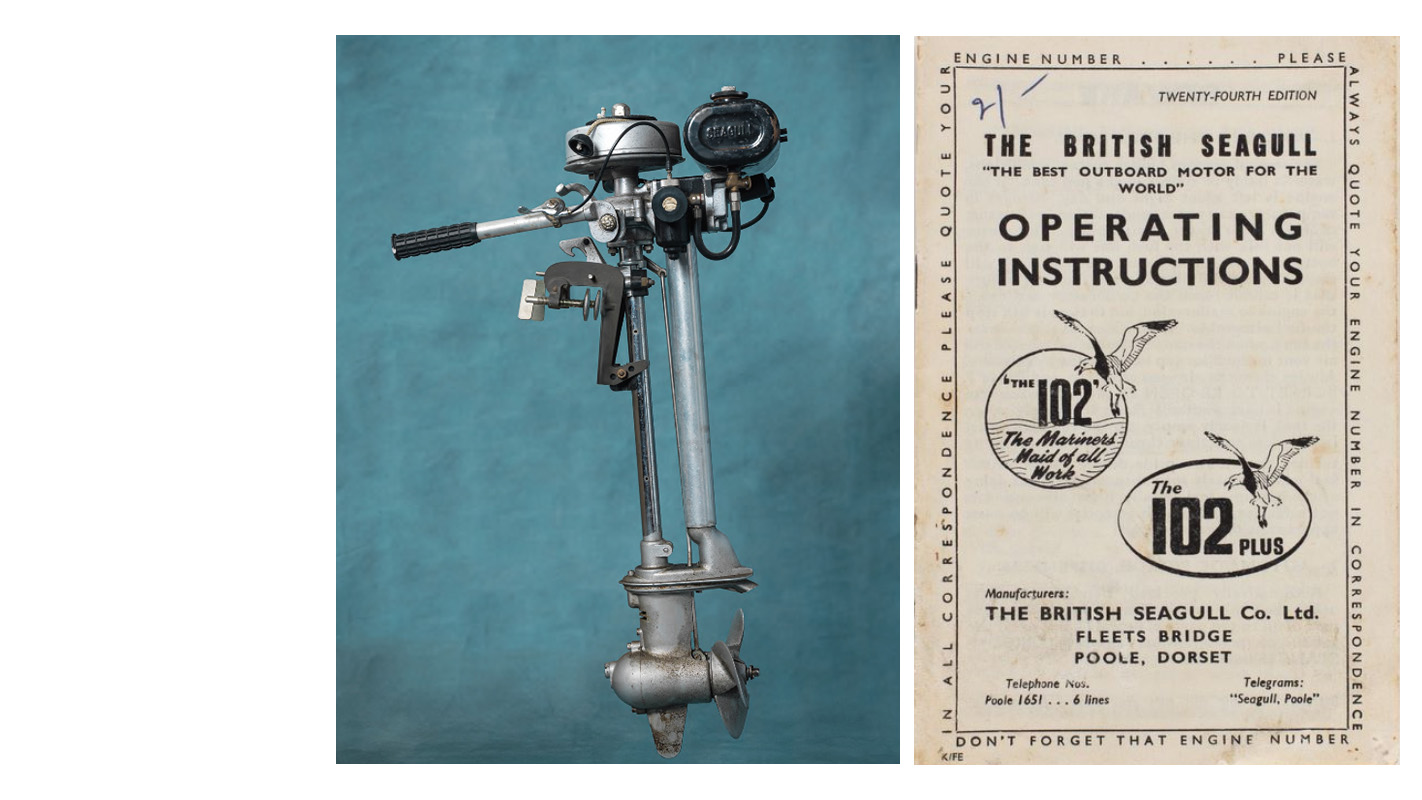

Made from high-quality materials, the outboard engine developed a reputation for rugged simplicity, having only three moving parts at the engine end of the shaft. Over the years several models were made: these included the 102cc; the 64cc Featherweight (AKA the Forty Minus); the 340cc; the Irish Seagull, with a water-cooled exhaust; and the Forty Plus clutch drive shown above.

Originally designed as workboat engine for the wooden boats of inshore fishers, the Seagull gained in popularity in the 1950s when small-boat cruising took off. The 1970s was its heyday; that was when 80,000 of the affordable bullet-proof motors sold annually as they were ideal for ‘pushing the tender, dinghy or the pocket cruiser along at a few knots when the wind dropped’, notes Classic Boat magazine.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, Seagull fans are competitive. A two-day Seagull regatta takes places every year on the 425-kilometre-long Waikato River. It began in 1985, to settle a dispute among locals as to who had the fastest gull-propelled dinghy. Further south, the Hatepe Seagull Caper takes place in Taupo every January. Participants are advised ‘if the lake is rough, we race in the river in heats. Short laps, two boats in each heat until we boil it down to the fastest boat and gull.’ Out west in Taranaki, the annual Waitara Seagull race takes place in the town, which has a shop called Simply Seagulls. Run by Jan and Graham Keegan, the business has 2000 customers around the country, and at any one time stocks about 100 working Seagulls as well of thousands of new and reconditioned parts. In a 2013 issue of The Gull—the official journal of the international British Seagull outboard owner—the Keegans described one fixture, called off because of torrential rain, but enjoyable nevertheless. ‘As one wag put it,’ the Keegans wrote, ‘what would you rather do: drive a smelly, smoky Seagull in the pouring rain, or sit in the Simply Seagulls workshop and have a few bevvies?

Environmentally now-frowned-upon outboards aside, over the next year the six-strong digitization team at the New Zealand Maritime Museum will liberate many objects from their current quarters in galleries and in store-rooms, illuminating our all-encompassing and sometimes surprising relationship with the sea. Some candidates are collections of: waka and Oceanic va’a models; yachting plans; booty from shipwrecks; candid diaries of 19th-century voyages; and delicate knotwork once fashioned by hard men.

Image Credits:

Forty Plus clutch drive outboard motor, British Seagull Co. Ltd., 1987. Photograph by Jane Ussher. ©New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa (2001.162.1). Gifted by B. Ballan.

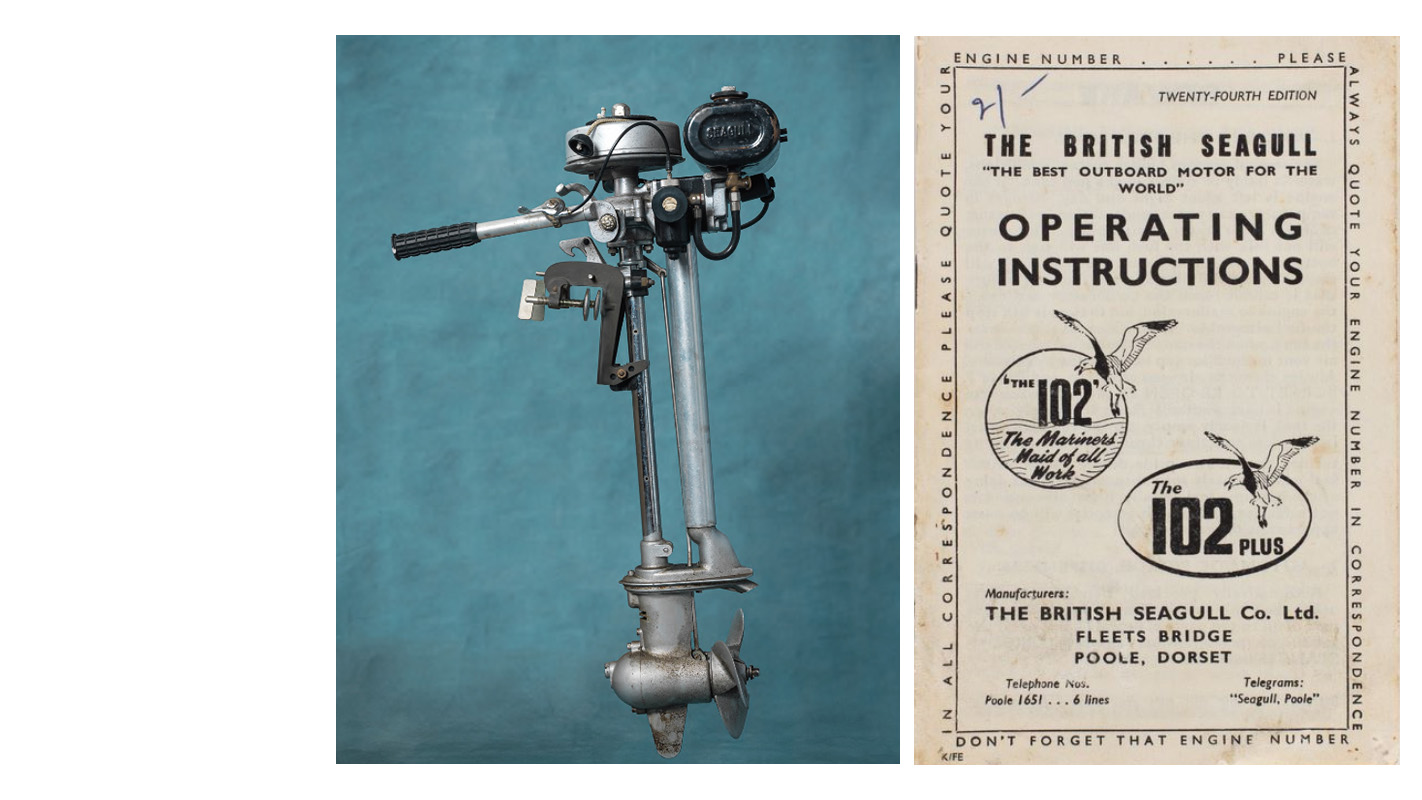

The British Seagull Operating Instructions The 102 Plus, 24th Edition, Circa 1960s. ©New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa (1996.68.2)

The above story is excerpted from: Endless Sea; Stories told through the taonga of the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui te Ananui a Tangaroa. Written by Frances Walsh. Photographed by Jane Ussher. Massey University Press, 2020.

References:

Charlton, Rex., Keegan, Graham., Keegan, Jan., & Walker, M. ‘Go the ‘Naki!’. Gull News, March 2013.

Meyric-Hughes, Steffan. ‘Seagull Outboards’. Classic Boat, May 17, 2011

*Have a story about a Seagull? We’d love to hear it. Contact: frances.walsh@maritimemuseum.co.nz