Seventy years ago, the National government sent armed forces onto the wharves in Auckland and Wellington to load and unload food and essential supplies from ships. Frederick Thomas was but one watersider, trade unionist, and citizen who likely saw the action as a double-barrelled assault on workers and democracy, and evidence that New Zealand was ‘under the iron heel of the police state’. 1

By Frances Walsh | 27 Feb 2021

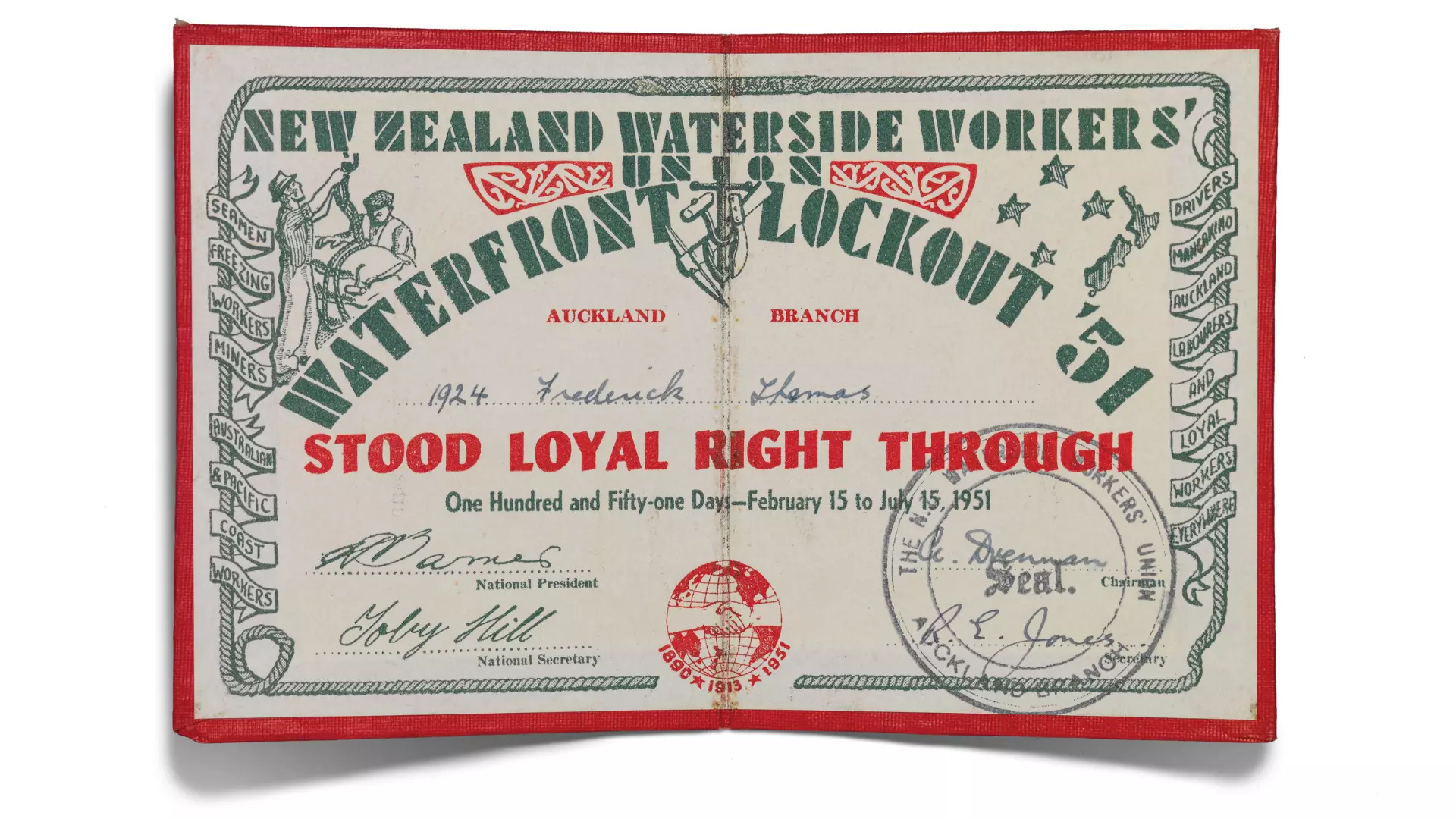

Frederick Thomas was a member of the Auckland branch of the New Zealand Waterside Workers’ Union (NZWWU) for at least 151 days in 1951, from February 15 to July 15. He was issued with the above hard-earned loyalty card to prove it, signed by among others the union’s national president Jock Barnes.

Thomas took part in the biggest and most costly industrial confrontation in Aotearoa New Zealand’s history: in a country of just under two million, 8000 watersiders and thousands of others who withdrew their labour in support of them, went without wages for five months. At the peak of the dispute 22,000 were off the job.

Historian Anna Green has argued that the dispute was essentially a battle between the NZWWU and shipowners for control of the wharves. It took place against the back drop of the Cold War—between the west and the Soviet Union—and when collective action was regarded with hostility even by the Labour government, whose ministers denounced the leaders of the NZWWU and the signatories of Thomas’s card as ‘communist wreckers’. And when the National government was elected in 1949, they promised to tackle unionism, head on.

The ultimate cause of the industrial confrontation was a wage dispute. After years of austerity, the economy was booming, but the cost of living was also soaring. In January 1951 the arbitration court awarded a 15 per cent pay increase to all workers; watersiders, however, were excluded as they were not part of the arbitration system. Instead, shipping companies offered them a 9 per cent increase. The NZWWU countered by refusing to work overtime—in the post-war period the high demand for shipping meant watersiders regularly worked overtime; in Lyttleton and Auckland, for example, they worked on average 50 hours a week. Employers told workers that unless they worked overtime, they could not work normal hours. The deal was refused, and watersiders were locked out. The country’s wharves came to a standstill.

Justifying that the New Zealand’s export trade was at risk, the National government declared a state of emergency, and Prime Minister Sydney Holland that the country was ‘at war’. Going beyond the rhetoric Holland deployed the army and navy to Auckland and Wellington wharves to shift cargo, and to West Coast mines to do the same with coal. It was also revealed in 2017 that the CIA flew cargo on covert flights between Wellington and Blenheim to help break the dispute, and the NZWWU.

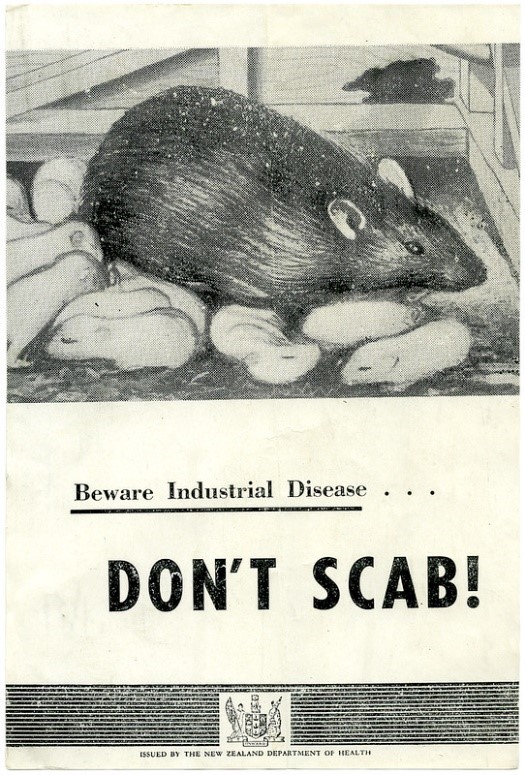

Emergency regulations hobbled the NZWWU’s ability to fight, imposing rigid censorship— which was nevertheless sometimes flouted with genius. On the night of 18 March, for instance, hundreds of ‘Don’t Scab!’ posters like the one below went up around Wellington. Seemingly they bore the imprimatur of the government, stamped with its coat of arms and issued by the health department. They called on workers not to break the strike, a.k.a. scab. The design subverted a previous health department flyer targeting the spread of disease, by using the same image of a rat family. The ruse sparked a major police investigation which saw civil servants and commercial printers questioned, and the houses of unionists raided.

Censorship wasn’t the half of it. The regulations also criminalized the giving of food to locked-out workers and their families. Police were granted sweeping powers of search and arrest, and the state was permitted to de-register unions and confiscate funds. The draconian measures attracted the ire of other unionists: miners in Huntly and on the West Coast of the South Island, freezing workers in Wairoa and Wellington, cement workers in Golden Bay, and 2000 seamen went on the strike for the duration of the lockout in support of the watersiders. As the dispute dragged on into winter, intimidation and violence became widespread. On 1 June—dubbed ‘Bloody Sunday’—1000 union sympathizers marched up Auckland’s Queen Street, and were laid into by police.

Eventually the government won the war of attrition; new unions of strike-breakers registered in the main ports, and the NZWUU was crushed and forced to split into small unions. Union members were blacklisted for years afterwards. Frederick Thomas’s loyalty card and others like it became for many a distinguished service medal.

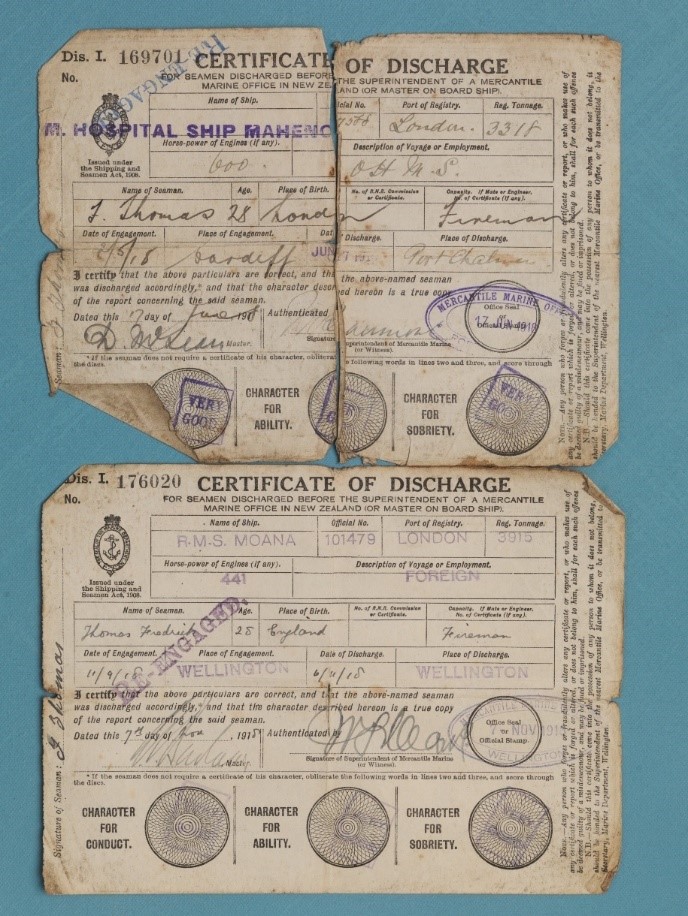

Just how Thomas fared during the lockout is impossible to say. The museum holds only a few of his papers and ephemera in its collection. In 1951 he would have been 61 years old. He may have worked on his union’s relief committee and at relief depots, or made and distributed propaganda on the QT. Similarly, his life before the events of 1951 can only be sketched—from several certificates of service and discharge on and from several vessels between 1918 and 1919.

They document him as being six foot one and of fair complexion. Sometimes he is recorded as being born in England, others in New Zealand. He crewed—often as a fireman—on RMS Tahiti, TSS Arahura, RMS Moana, and SS Kaitangata. He joined ships at Onehunga, Auckland, Wellington, Port Chalmers, and Cardiff. From his collection of postcards, he looks to have stretched his legs around Sydney, Newcastle, Hobart, the Marquesas Islands, San Francisco, and Port Said in Egypt. And he deported himself well, consistently receiving a ‘Very Good’ stamp for conduct, ability, and sobriety.

1. Dick Scott, 151 Days (Auckland, NZ: NZ Waterside Workers’ Union (Deregistered), 1952), 39

Image Credits:

NZ Waterside Workers’ Union Waterfront Lockout ’51 card belonging to Frederick Thomas. Dick Scott & Max Bollinger designers, 1951. Photographed by Jane Ussher. ©NZMM (1994.258.9)

Fry, Alexander Sydney. ‘Beware industrial disease…Don’t Scab’. 1951. Ephemera Collection Eph-A-LABOUR-1951-03. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Certificates of Discharge from Maheno & RMS Moana for F. Thomas, 1918. Photographed by Jane Ussher. ©NZMM (1995.38.7)

References:

Derby, Mark. ‘Strikes and labour disputes: The 1951waterfront dispute’, Te Ara-the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Green, Anna. British capital, Antipodean labour, University of Otago Press, Dunedin, 2001

Millar, Grace. ‘Families and the 1951 New Zealand Waterfront Lockout’. PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2013.

Scott, Dick. 151 Days: Official history of the great waterfront lockout and supporting strikes, February15—July 15, 1951. NZ Waterside Workers’ Union (Deregistered), Auckland, 1952

‘The 1951 waterfront dispute’, Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Know something of Frederick Thomas? We’d love to hear it.

Contact: frances.walsh@maritimemuseum.co.nz