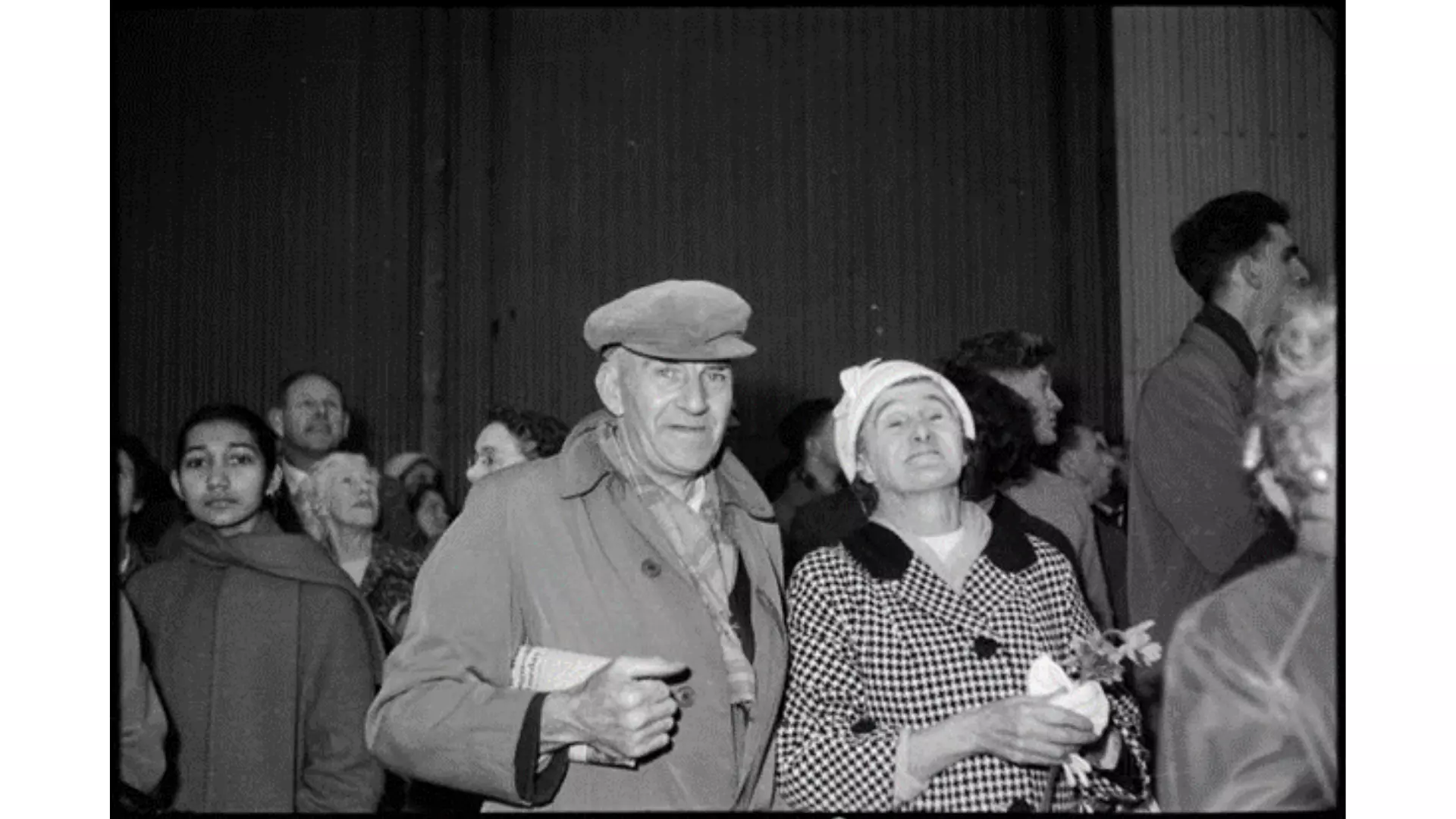

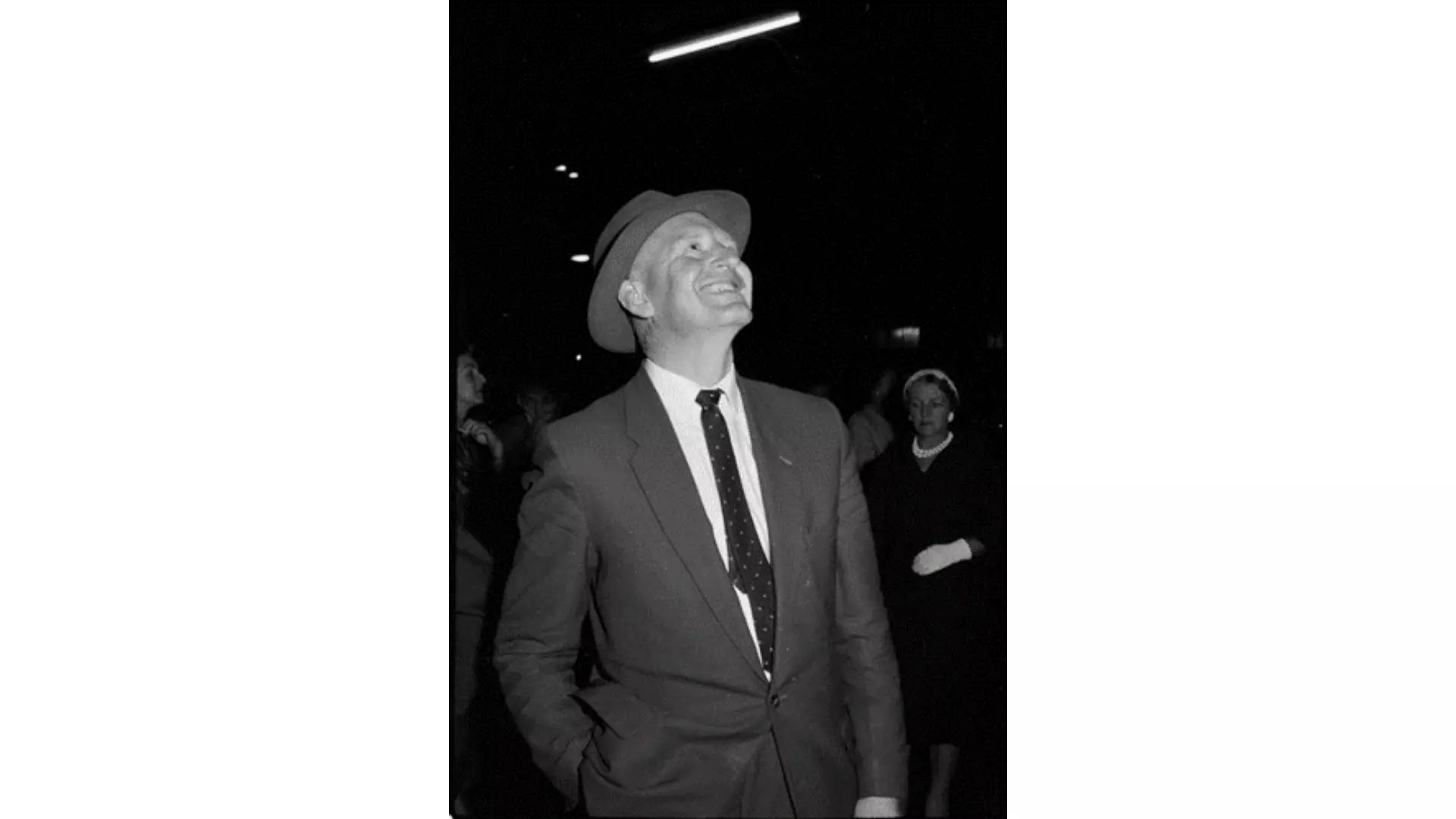

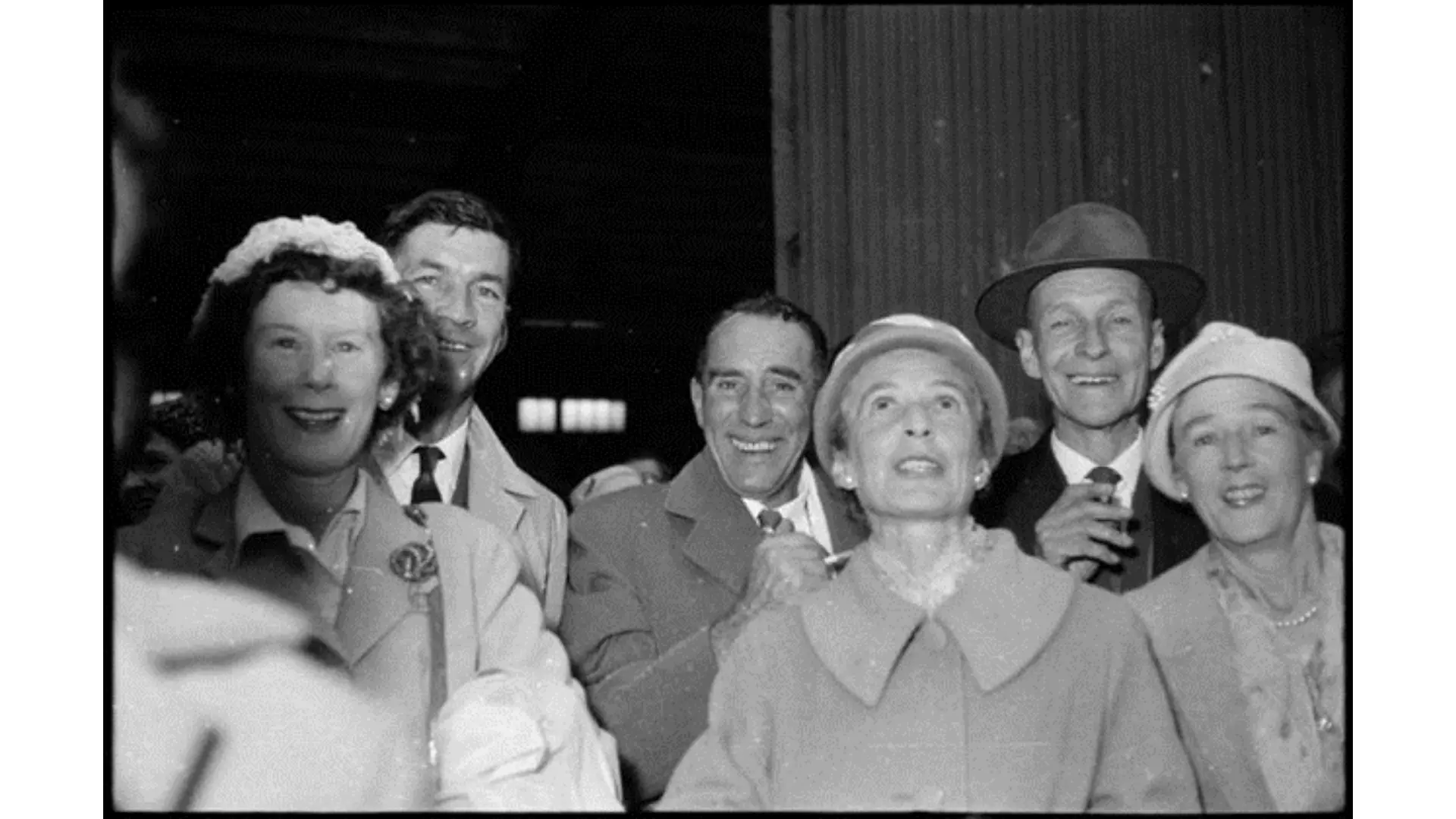

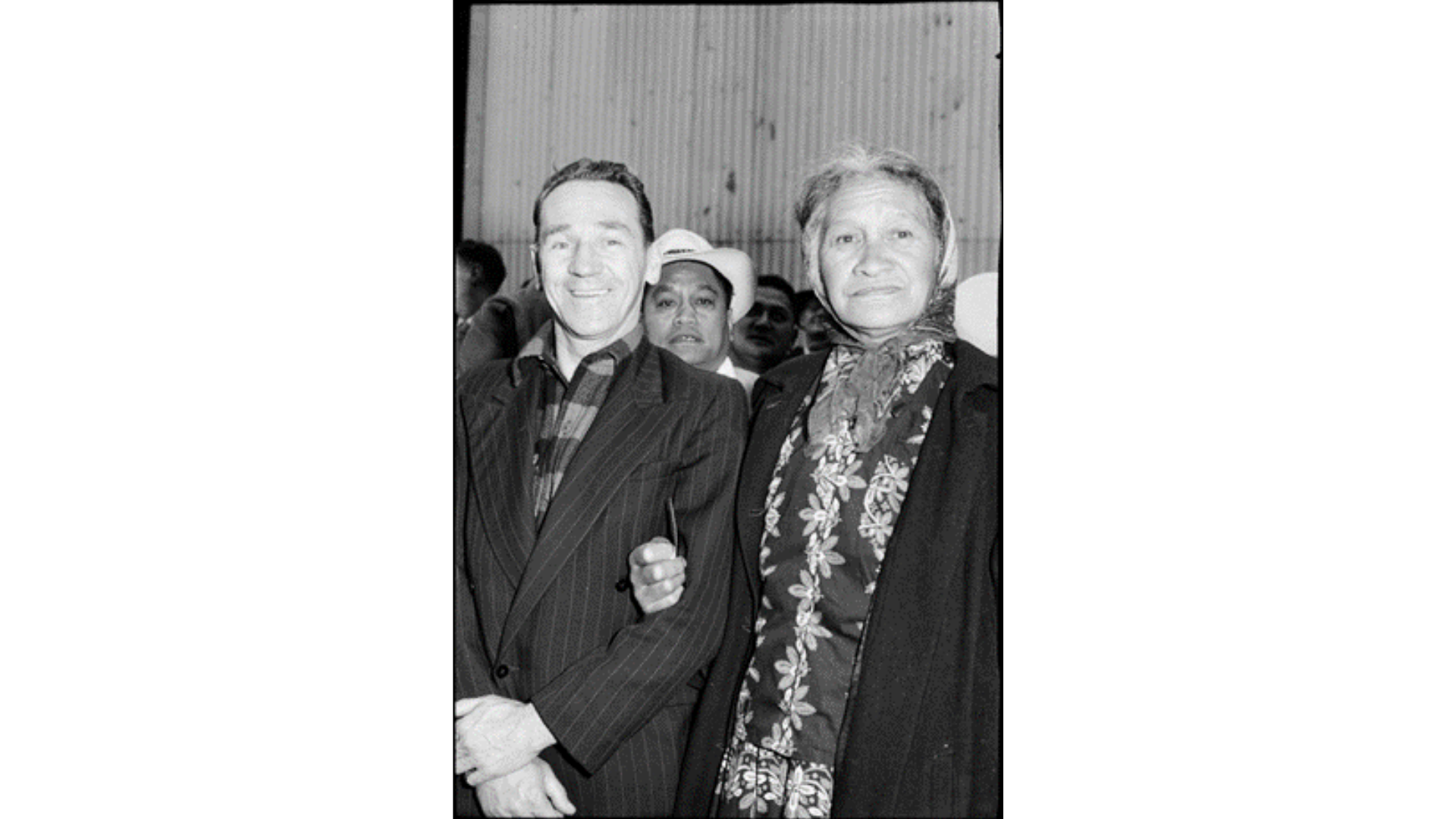

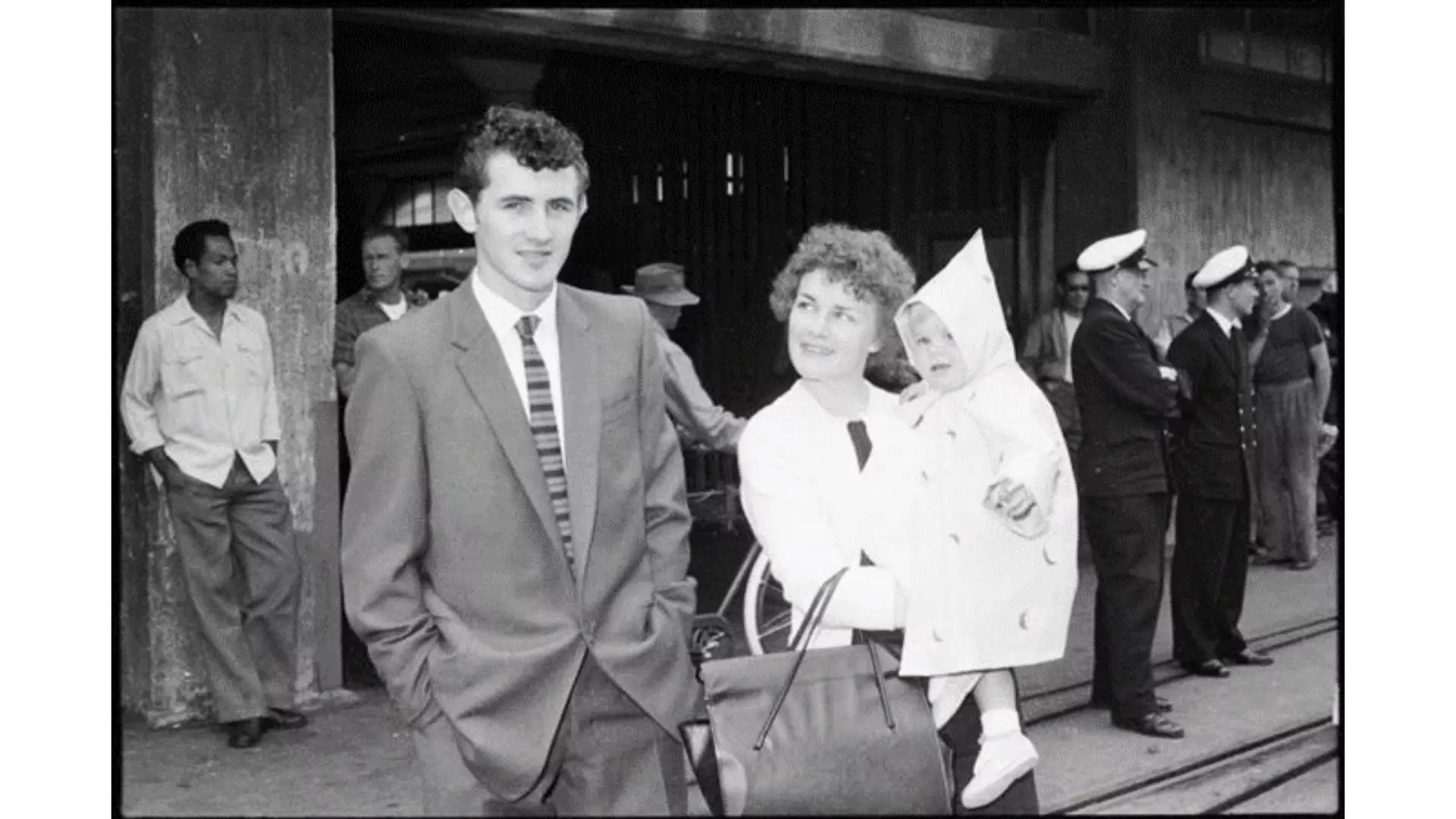

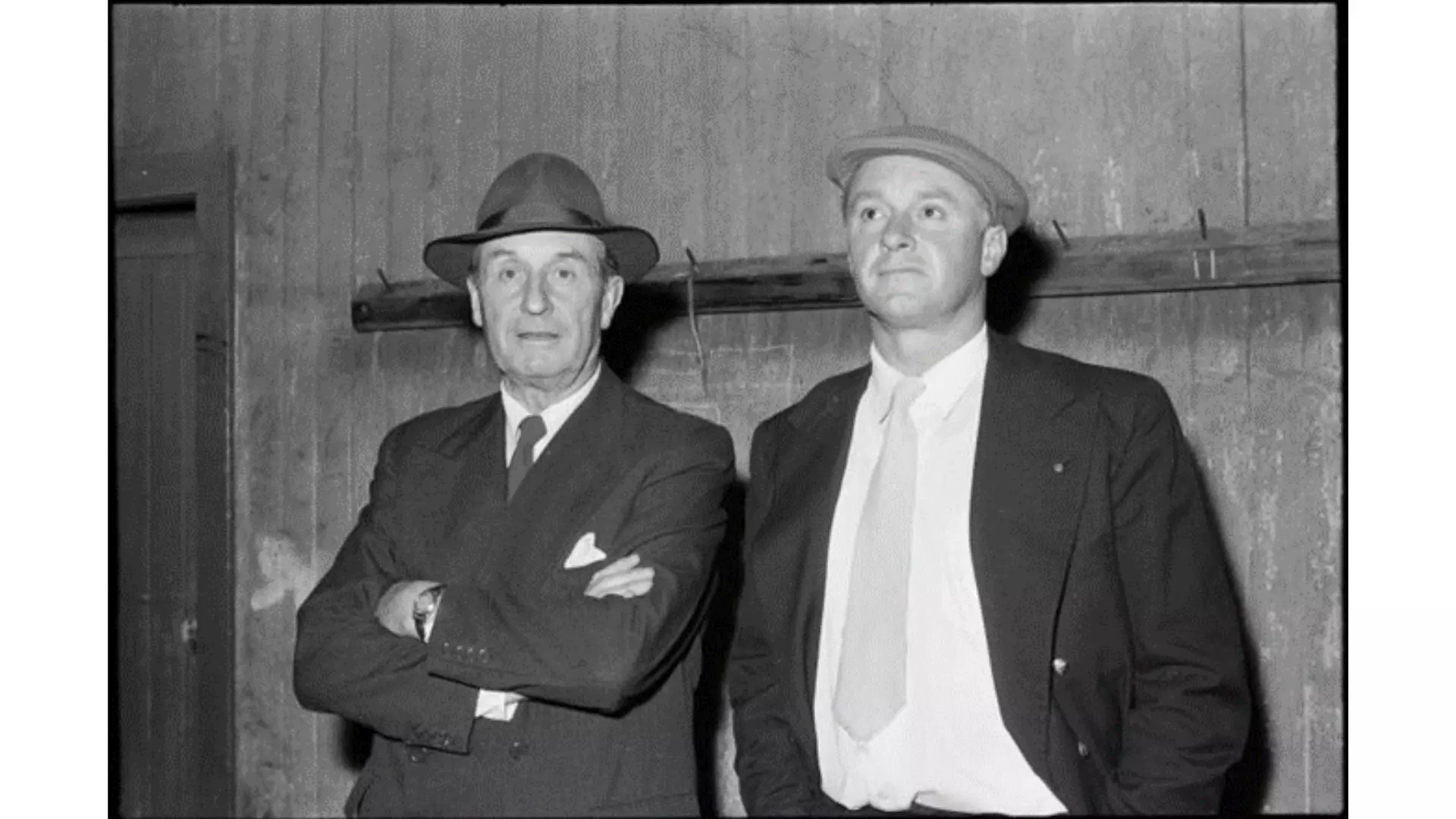

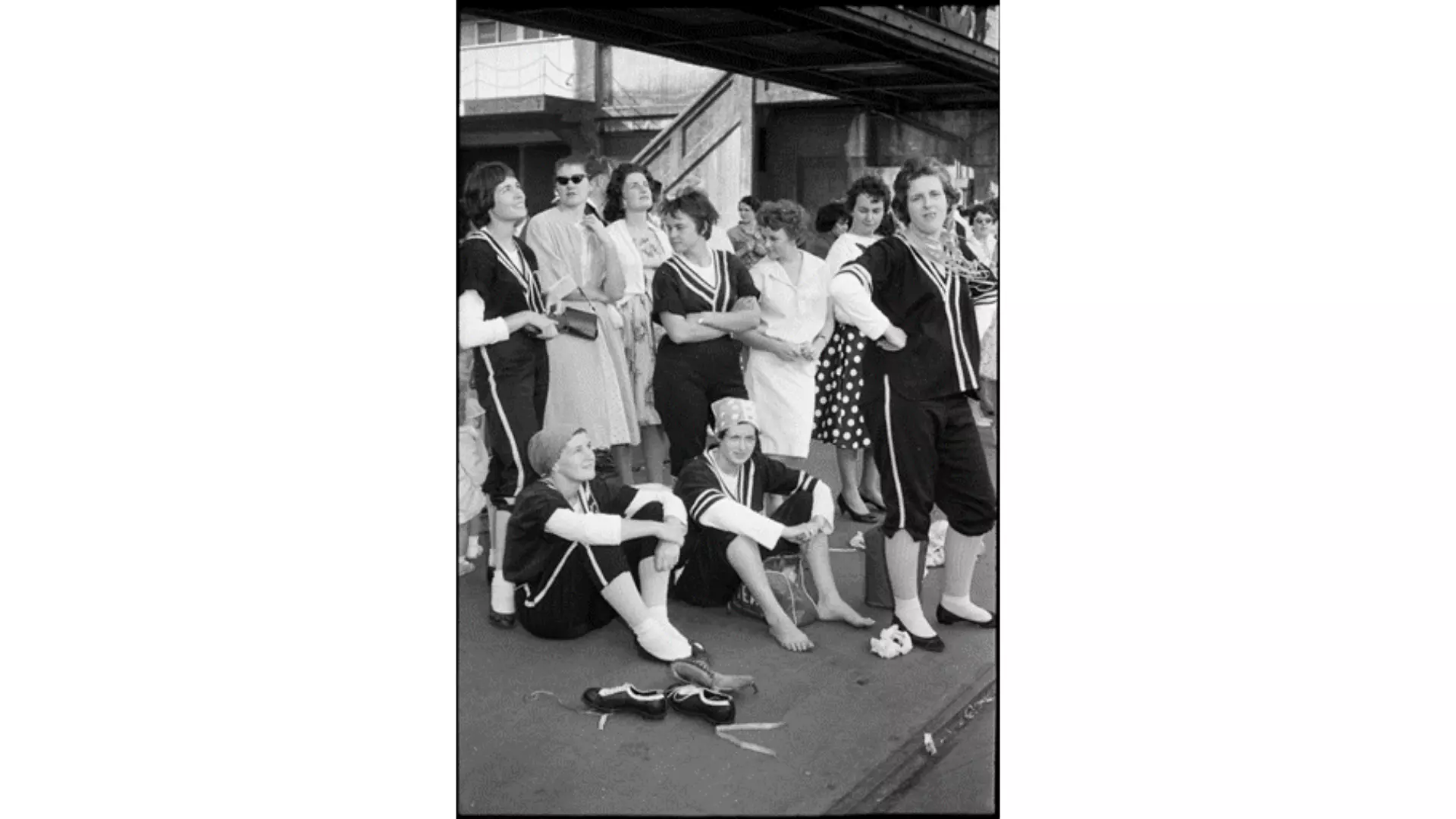

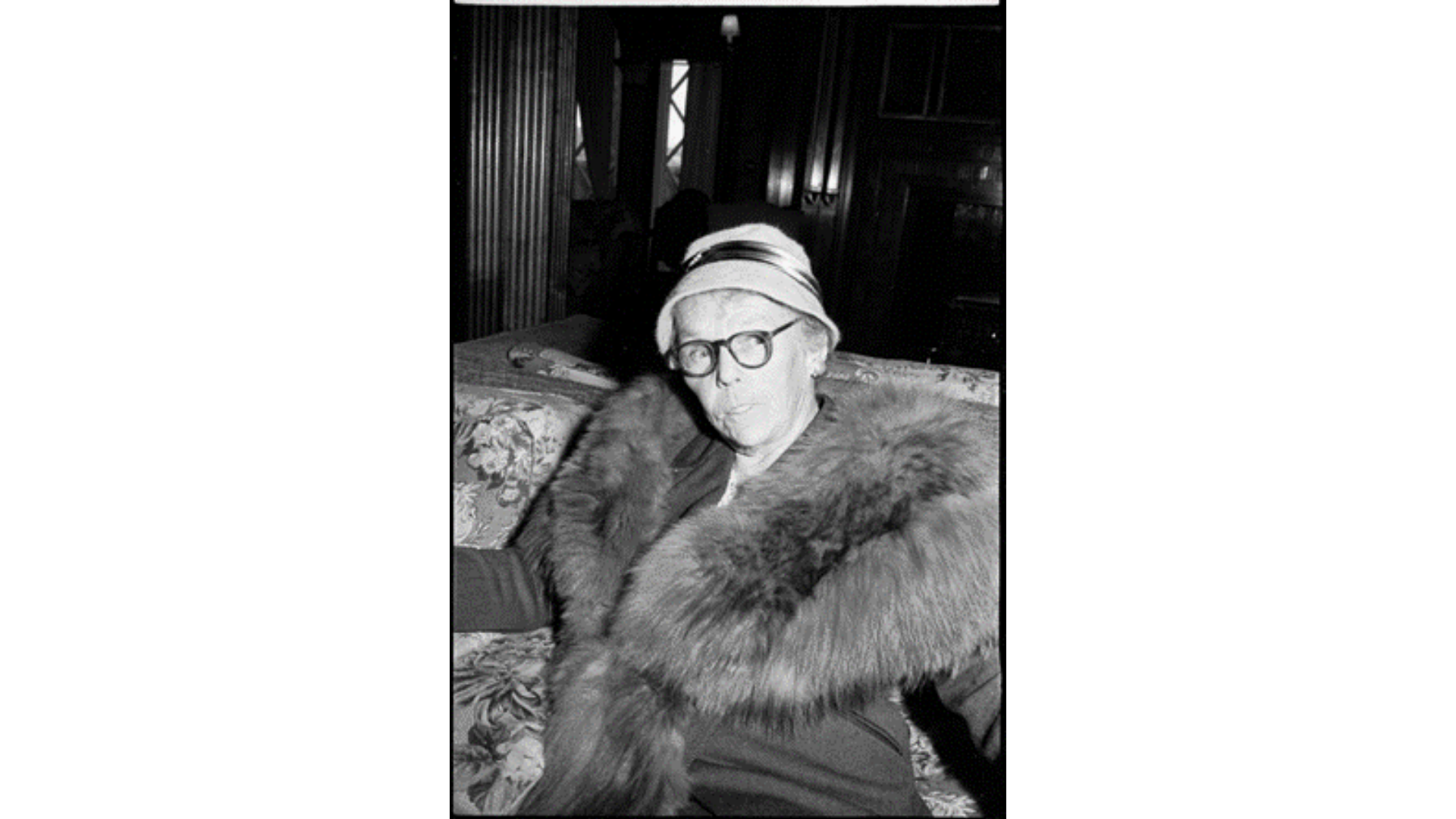

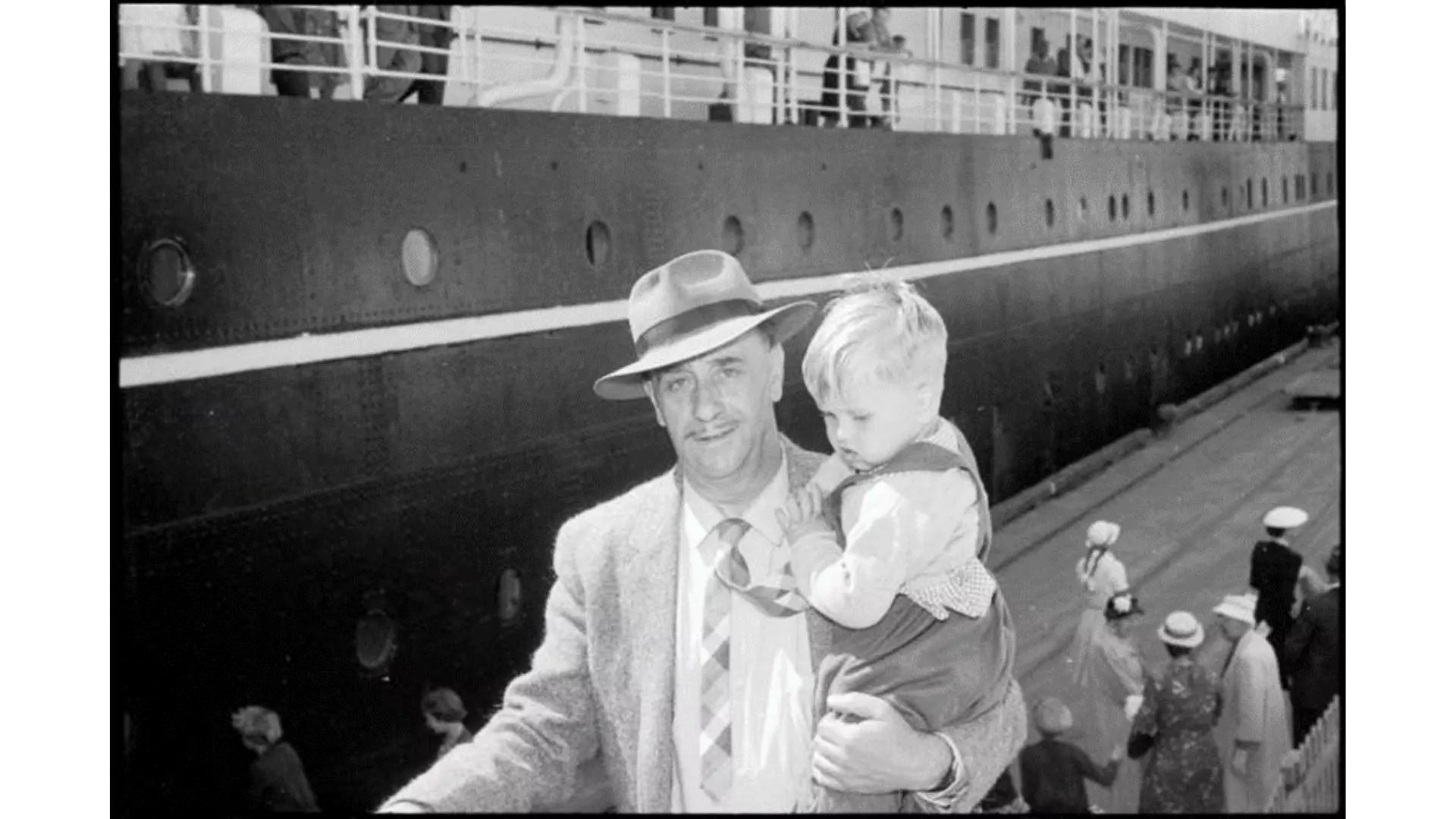

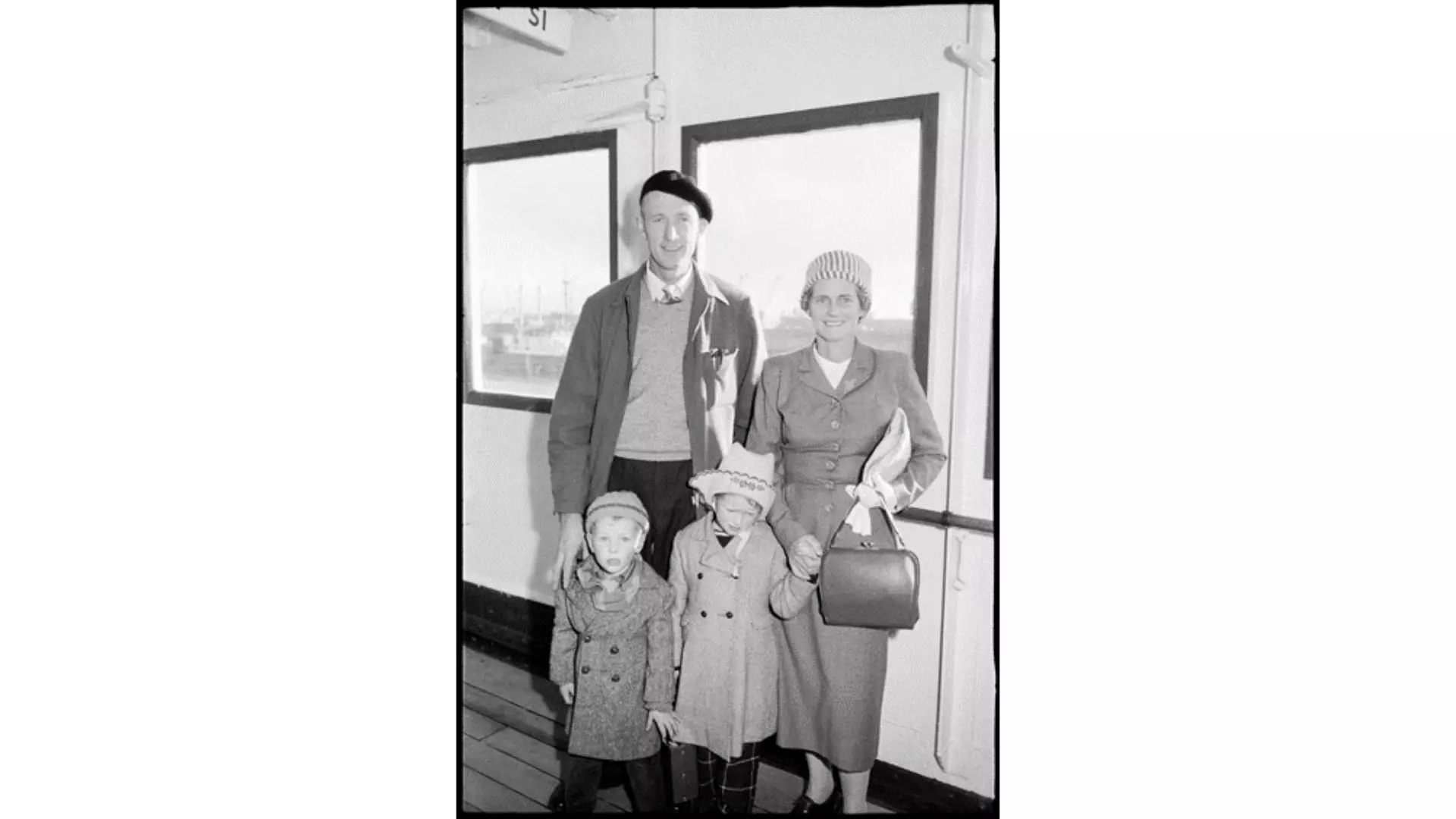

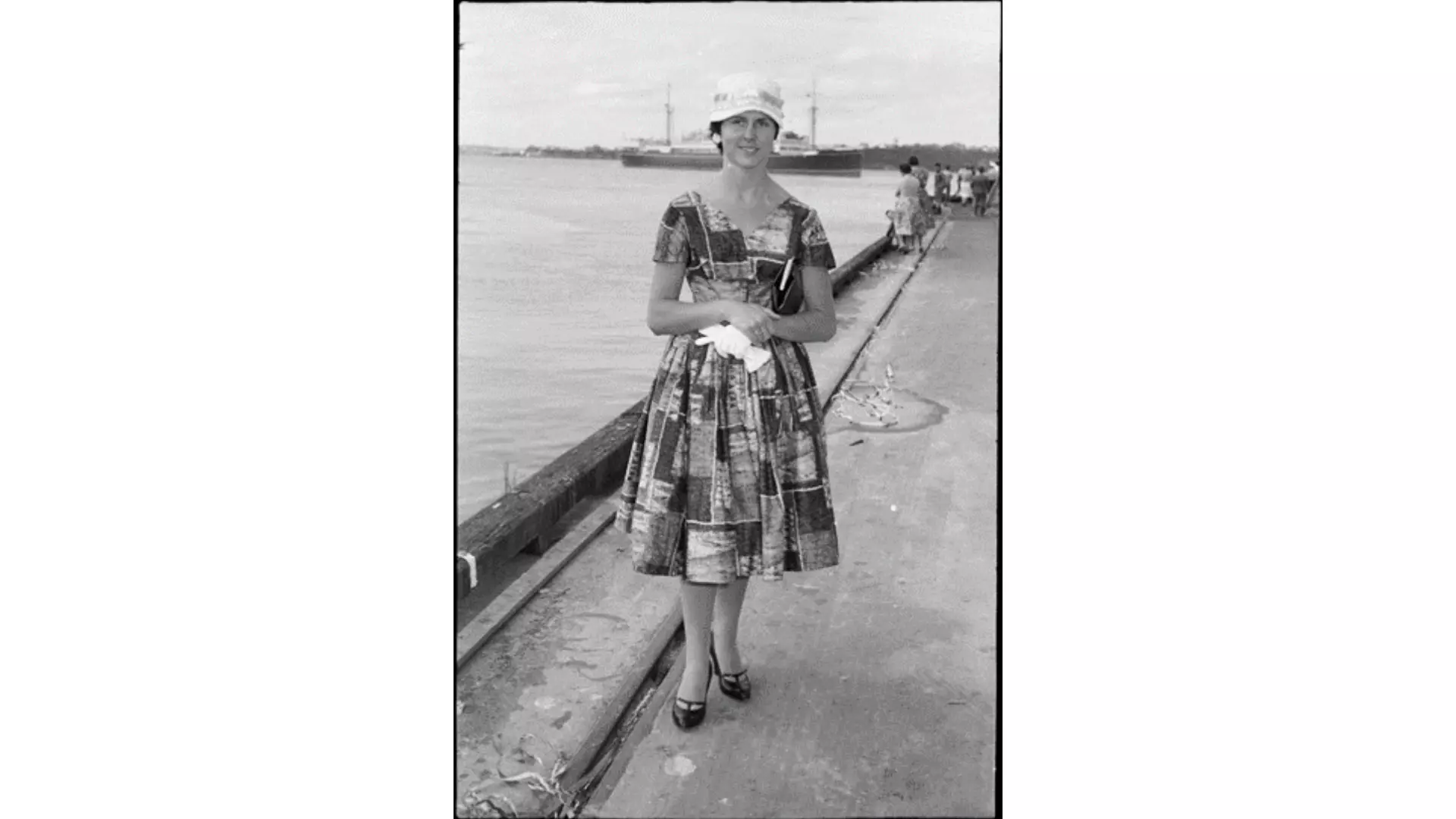

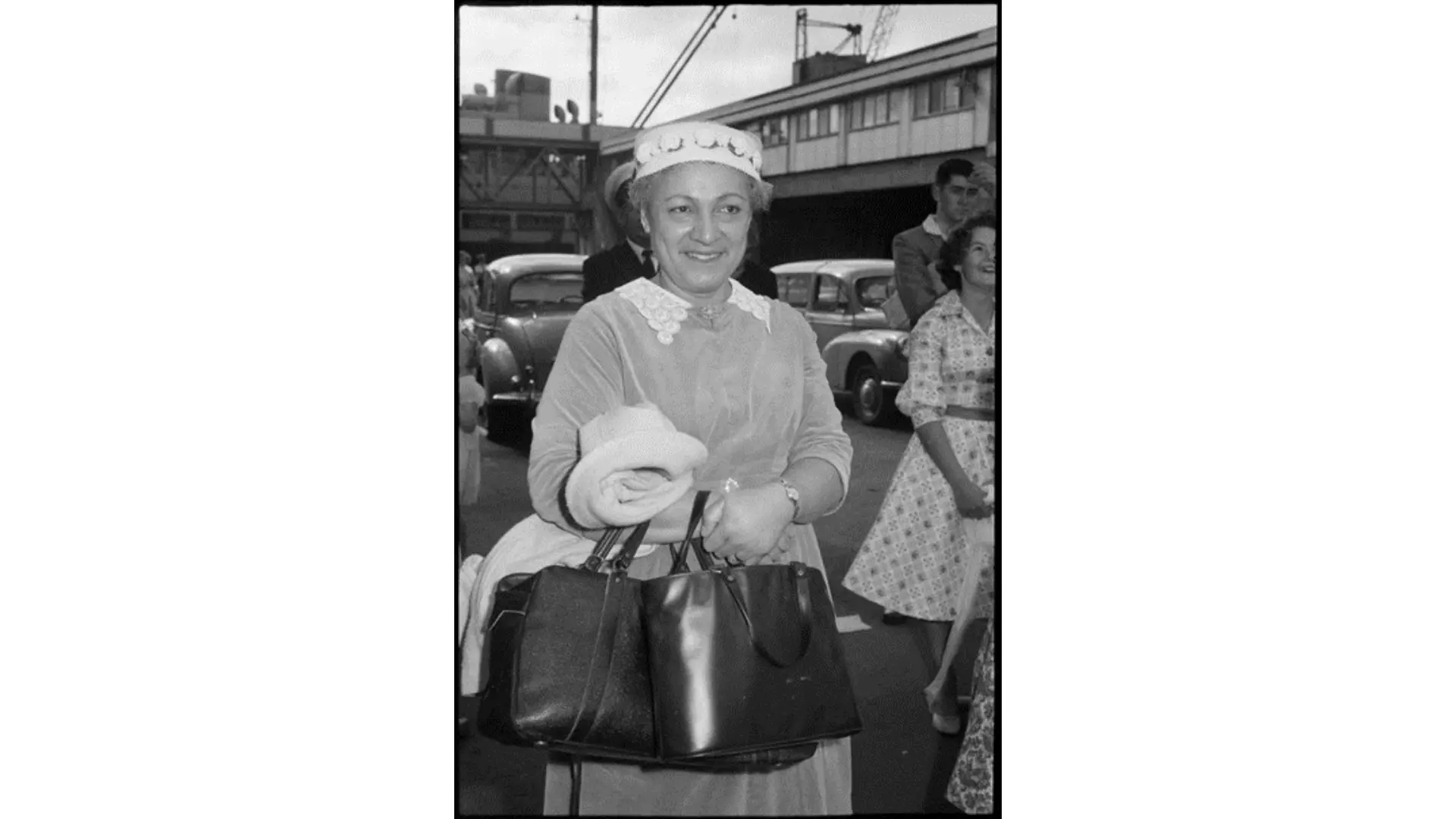

On the wharf and in ships Rykenberg had his favourite vantage points; he memorialised subjects propped against graffitied walls and corrugated-iron sheds, alongside ships, backgrounded by the Waitematā, ascending the gangway, on decks and in lounges. Non-travellers could go aboard and check out the ships’ interiors, until the ‘All Visitors Ashore’ announcement boomed. In the case of Wanganella and Tofua 11 upholstery featured chintz. And then some. Women in patterned outfits and hats which kicked it up a notch with flora and shaved-rooster feathers were subsumed into settees.

Although Rykenberg didn’t see himself as a social documentarian, his series of 1959-1961 photographs shown here record a last hurrah. Shipping lines faced dwindling passenger numbers as far swifter long-range air travel took over. In 1966 Auckland’s international airport opened and the newly formed Air New Zealand acquired three DC8 jet aircraft for a trans-Pacific service. Wanganella was withdrawn from the trans-Tasman route in 1962; the New Zealand Shipping Company halted its service to and from Britain in 1968, and retired Rangitane; and Tofua 11, on the Pacific Island run since 1951, was the last passenger-cargo liner built for New Zealand’s Union Steam Ship Company.

As for the hats, it was soon goodbye to all that too, or at least to headgear as an essential accessory. In 1960, under the industry category of ‘hats, caps, and millinery’ the New Zealand Official Yearbook recorded 54 establishments, and more than 1000 workers; by 1975 headgear was manufactured in 25 establishments, by 300 workers. One or two-person independent milliners and hatters were not captured in the statistics but they suffered a similar hit.

The reasons for the decline were various. For men in particular increasing car ownership had an effect, and broke the habit; no need to have a hat to keep the head warm and dry, and roofs were hat-crushing besides. Compelling blokes also began to go hatless—John F. Kennedy, for example. For women the bouffy coiffeurs of the 1950s which reached for the skies were a disincentive, as was the1960 beehive, invented by the Chicago stylist Margaret Vinci Heldt and inspired by a fez, a felt hat commonly worn in the Ottoman Empire, and occasionally on Auckland’s Princes Wharf.

Fashion generally became more informal, and second-wave feminists, youth, and hippies preferred ease of movement. Christian Dior’s 1947 clinched waist, full-skirted ‘New Look’ frocks were eased out by the waistless shift, credited to Coco Chanel in the 1920s. Compelling females also went hatless. In 1965 the model Jean ‘The Shrimp’ Shrimpton went to the Melbourne Cup in a white shift dress. The day after Melbourne’s Sun News-Pictorial reported: ‘There she was, the world's highest paid fashion model, snubbing the iron-clad conventions of fashionable Flemington with a dress five inches above the knee, NO hat, NO gloves and NO stockings!’ The London Evening News retaliated: “...surrounded by sober draped silks and floral nylons, ghastly tulle hats and fur stoles, she was like a petunia in an onion patch.’ In her 1990 autobiography Shrimpton noted that in 1965 she didn’t own one hat.

*The museum is keen to identify people in the photographs shown here, and to reunite them with their whānau. If you have any information please contact frances.walsh@maritimemuseum.co.nz. The museum thanks Wendie Wright and family and Auckland Libraries, which holds all the photographs shown here in its heritage collection. To see more Rykenberg photographs search https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/