Bean Rock lighthouse became the first lighthouse in New Zealand to be demanned and automated in 1912; in 1990 all lighthouses became remotely monitored in Wellington by Maritime New Zealand. But the Andersons had vamoosed before the axe fell on Bean Rock—transferring to the lighthouse at Manukau Heads in 1911. Ivan was to tell Paul Shirley decades later in the 1970s that the family ‘were pleased indeed’ to leave. The difficulties of the living arrangements aside, the family had had a sad two-year stint in Devonport on Bean Rock: 7-year-old Rosslyn Anderson and 16-year-old Dorothy Anderson had both died.

By 1917 the Anderson family had upped sticks again, and were installed in a house overlooking Te Ara a Kiwa Foveaux Strait while James operated the beacon at nearby Waipapa Point. The location may have caused some initial trepidation. A previous keeper, William Nicholson, had taken his own life, the Southern Cross reporting in 1903 that 'The deceased, who was highly esteemed, had been engaged for many years in the service, and the comparative isolation had told on his nervous system, and lately he had suffered severely from sleeplessness.’

It was while living at Waipapa Point that the teenage Ivan had another brush with tragedy, making the Bruce Herald in April 1917. He found a barnacle-encrusted bottle on the beach. Inside was an envelope on which was written: ‘Thrown overboard at 9.30am, Friday, August 25, 1916. Message enclosed. ‘Everybody’s happy.’ On opening the envelope Ivan read the following message: ‘NZ Expeditionary Force, August 25, 1916. At Sea, Troopship 61. To the finder of this message: Please communicate with Australian and NZ [news]papers: All well on board; good weather; plenty of good tucker. Left Wellington, New Zealand on August 20. No sight of land yet . . . Kia ora. H.A. Aldridge, G. Haslett, N. Vercoe, M. Henderson, Harry Hammerill, Geo. Wahlstrom, W. Rankin, T. Ernest, D. Clemo, F. Dotter, H. Aldridge (all Aucklanders).’

Troopship 61 was Aparima. It had left Wellington eight months before Ivan’s lucky find, and was probably in Australian waters when the crew hurled their cheery communique overboard. Only months after the Bruce Herald write up Germans torpedoed the ship in the English Channel killing 54 of the 110-strong crew.

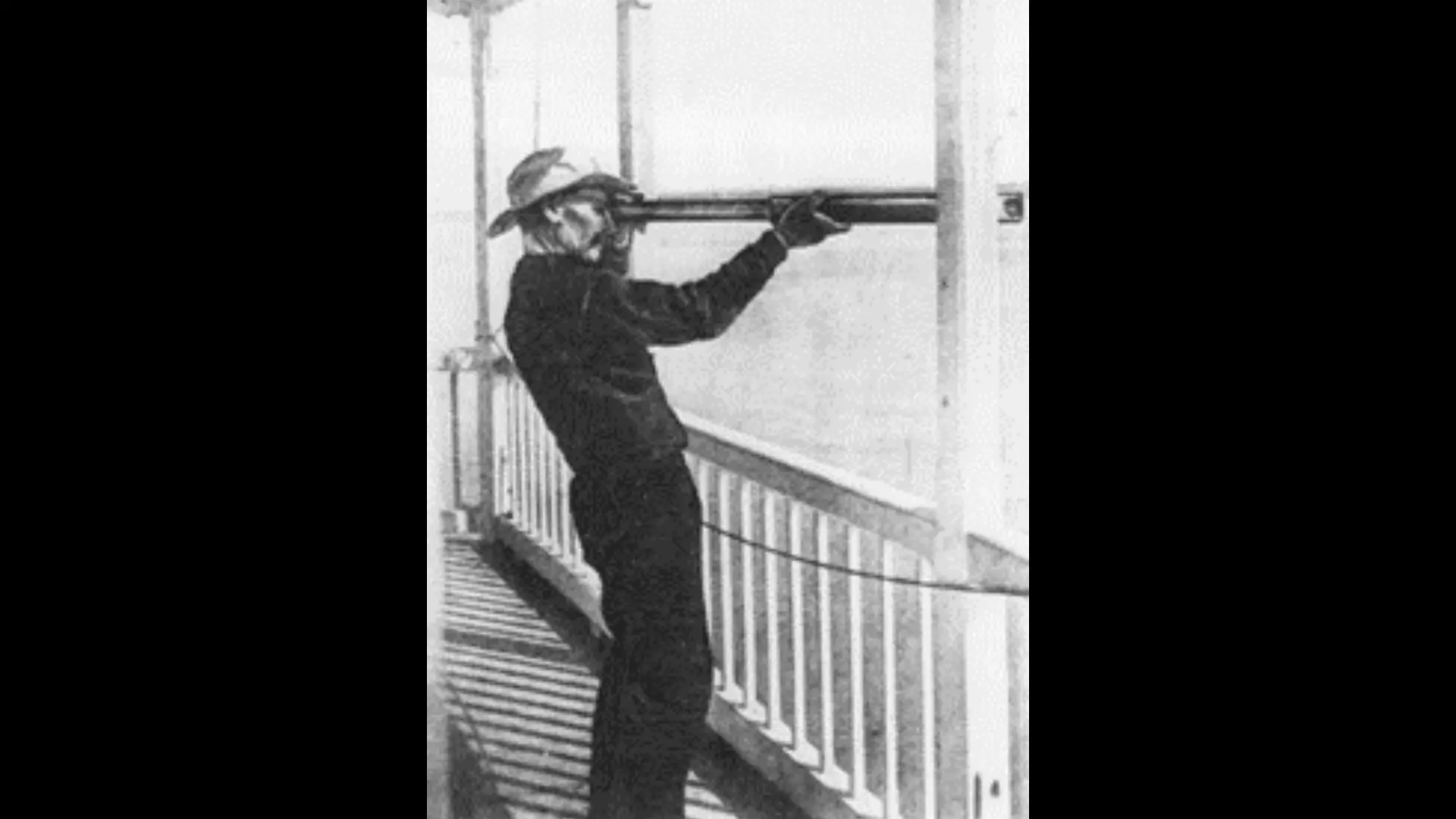

Ivan joined SS Hinemoa and Captain John Bollons in 1917 as a boy seaman, and kick-started a 40-year career with the Marine Department. He subsequently served in another government steamship Tutanekai. For a time he was in charge of the launches servicing staffed and unstaffed lighthouses around the Hauraki Gulf and Te Tai Tokerau—by the late 1950s all the main lights in New Zealand had been electrified; by the 1970s only six lighthouses had full-time residential staff.

When looking back on his life in 1971, then a retired fisheries officer living in Russell, Ivan wrote: ‘For many years now, keepers had no need to keep watches in any of our lighthouse towers, and to go into a tower at night with no noise of machinery, hiss of the incandescent light, and no familiar tea-billy hanging above the table-lamp to keep tea warm. To me, there is a lot missing in the atmosphere, and instead of homeliness, there is a chill of loneliness. Once again the march of progress, but to our family and especially myself, they were happy times, spent in what were once outlandish places and to many, considered very lonely.’ Ivan also noted he had picked up a familial habit: ‘My father was always a keen naturalist in his own way, and also keen on Maori history and a collector of artifacts. I followed in his wake . . . and have a good collection of Maori curios from the full length of New Zealand.’

References:

“A Lighthouse Keeper’s Death”, The Southern Cross, 19 Sept 1903, 5

Anderson, Ivan. “Life in Lighthouses”, Nelson Historical Society Journal, vol 2, issue 6, April 1973

“General News”, The Southern Cross, 12 Sept 1903, 8

“Clutha News Items’, Bruce Herald, 16 April, 4

“History of New Zealand lighthouses and their keepers”, Maritime New Zealand. Retrieved 8 Nov 2022: https://www.maritimenz.govt.nz

“Personal”, Manawatu Standard, 23 June 1928, 9

Shirley, Paul W. “Guardian of the Waitemata Harbour: A History of the Bean Rock Lighthouse”, c. 1977. Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum, MS-991

Sheehan, Grant. Ivan and the Lighthouse. Illustrated by Rosalind Clark. Phantom House Books, 2016