By Frances Walsh | July 2024

A version of this handkerchief received the thumbs-up from The Army and Navy Gazette in 1895, in the days when the accessory now regarded as a cult relic was ubiquitous. But rather than a nose-wipe or decoration, the large handkerchief was designed to be an aide-mémoire.‘The notion is good and has been well carried out, both from an artistic and educational point of view,’ the London-based gazette assessed, predicting the well-resolved item would become ‘an indispensable adjunct to every seaman’s kit’.

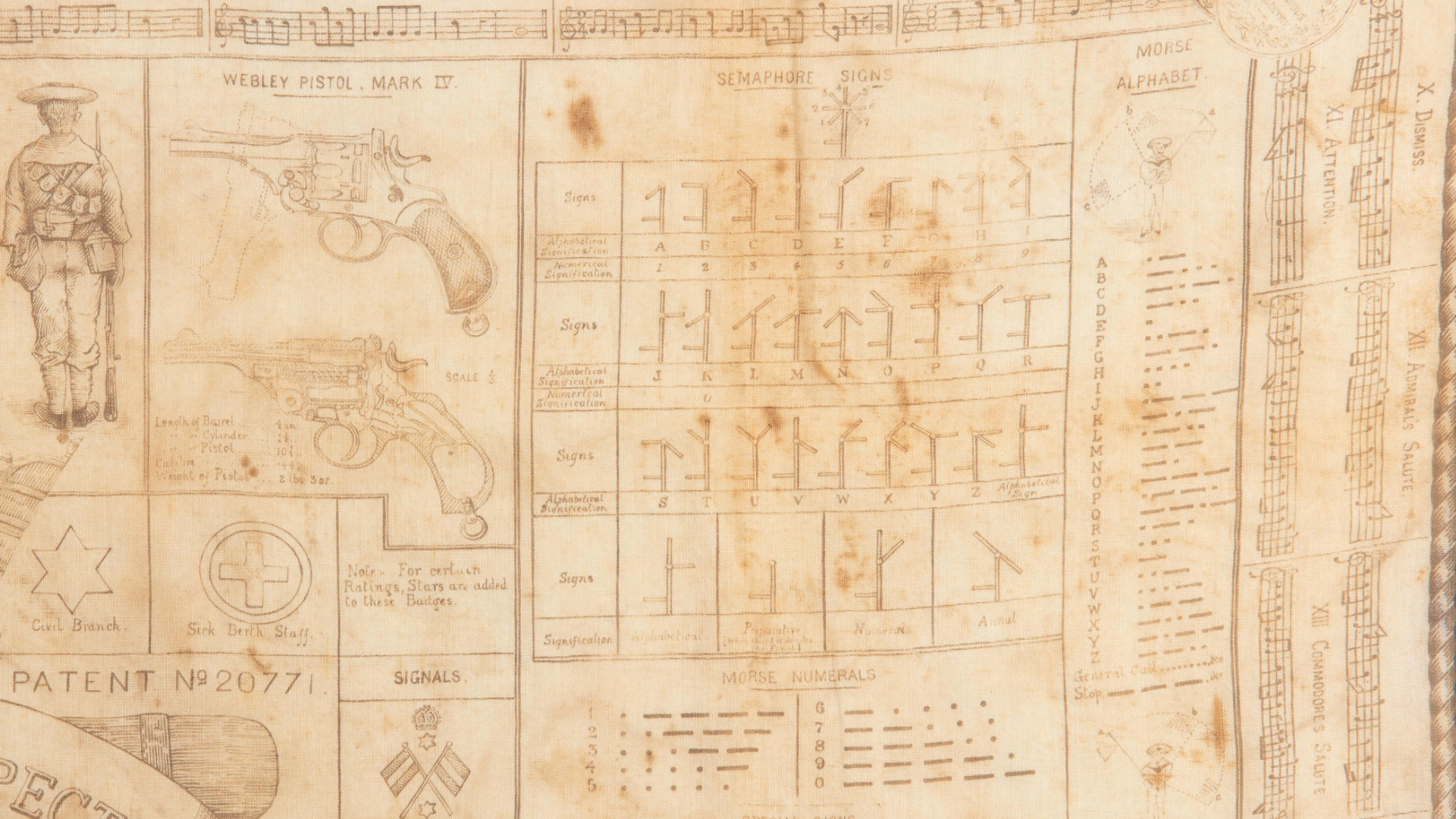

It’s chokka with information, useful to those involved with the ongoing and bloody expansion of Britain’s imperial holdings in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At its centre is a misquote of Admiral Horatio Nelson’s signal to the British fleet, flown as action commenced against the combined navies of France and Spain off the province of Cádiz, at 11.30 hours on 21 October 1805: “England Expects That Every Man This Day Will Do His Duty”.

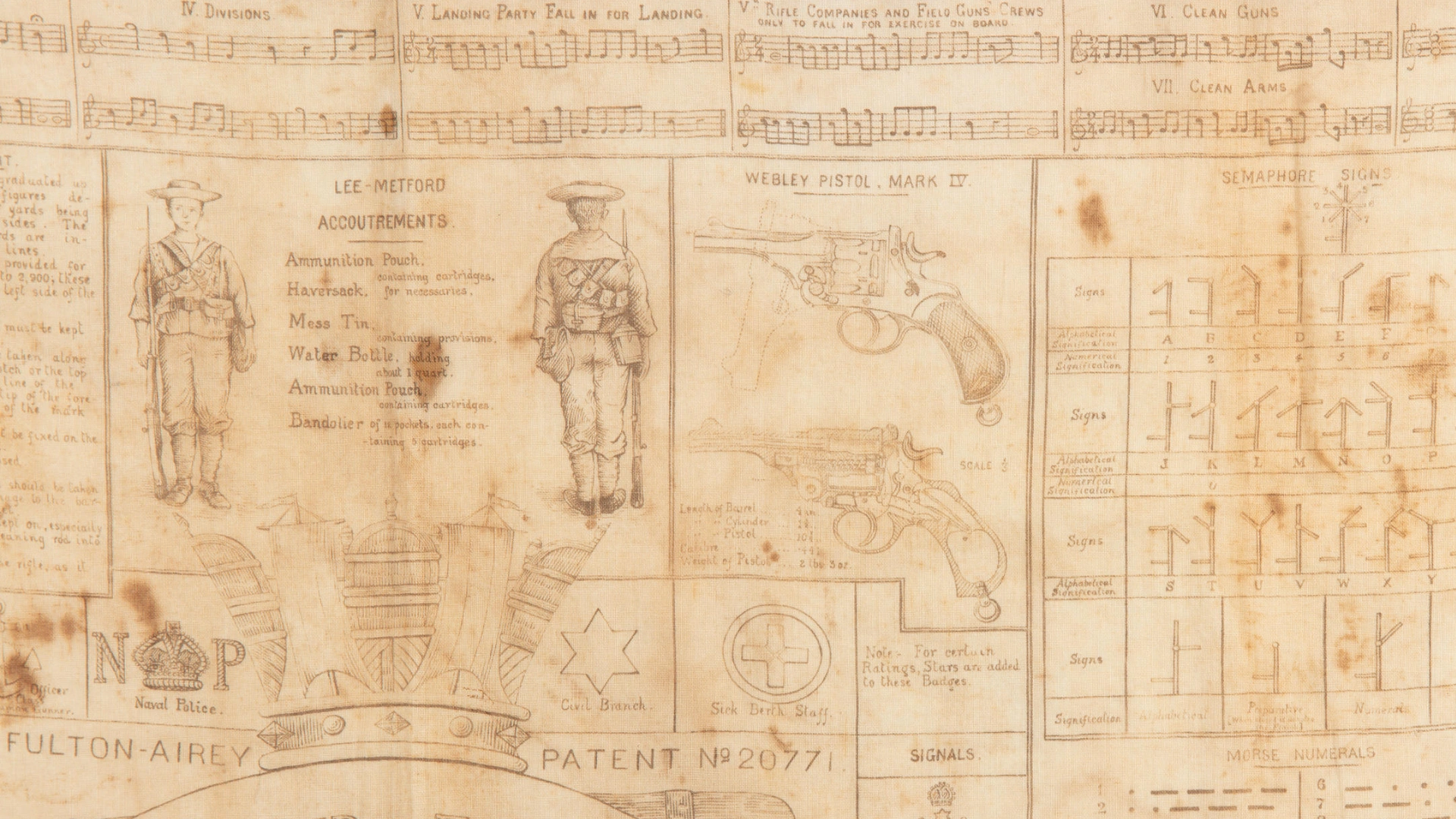

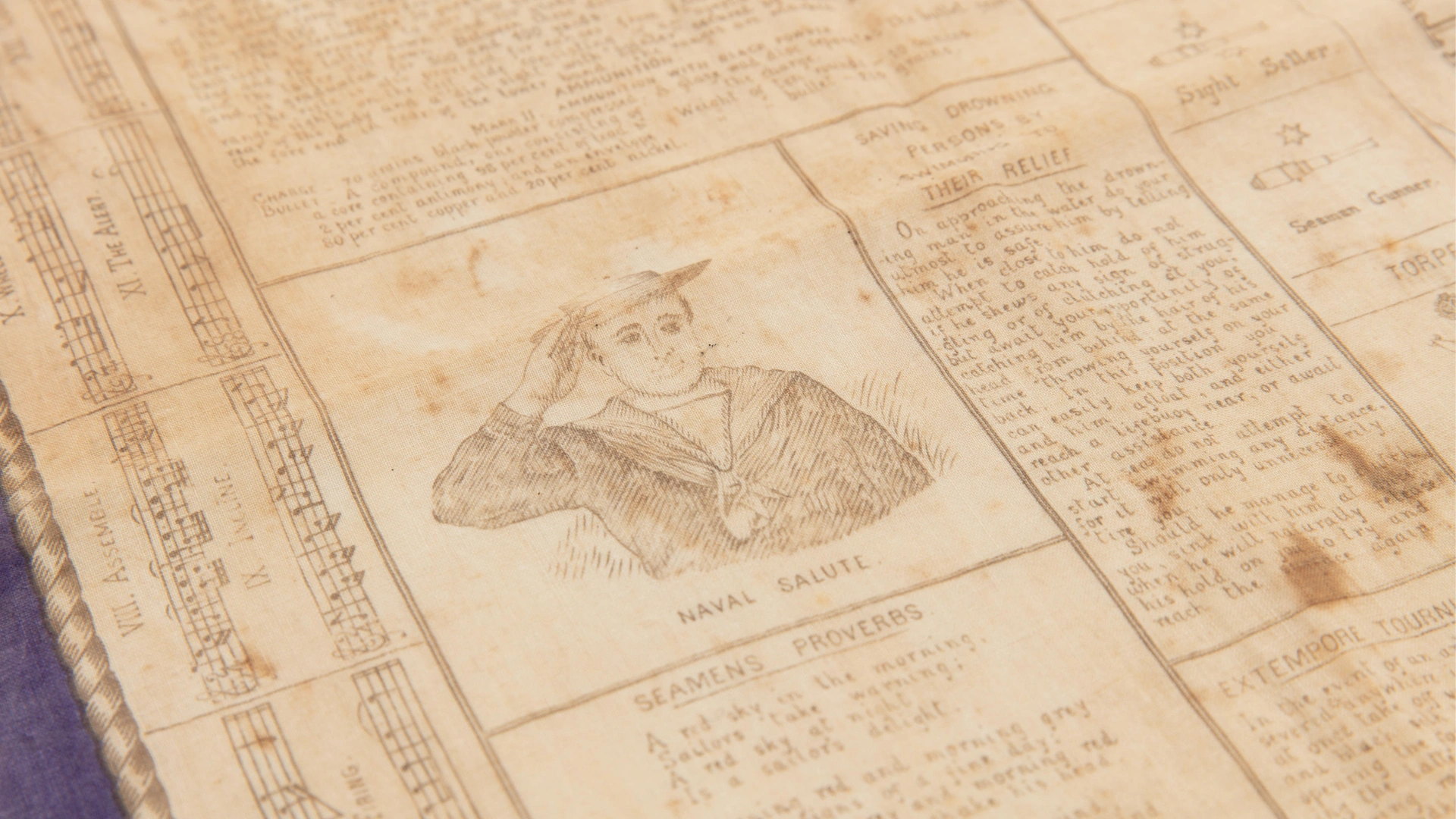

Illustrations and descriptions surround Nelson’s Battle of Trafalgar gee-up—of: the Lee-Metford Mark II bolt-action rifle; the Webly pistol Mark IV; exercises for developing sword-fighting proficiency. Life-saving techniques are explained—under the headline SAVING DROWNING PERSONS BY SWIMMING TO THEIR RELIEF: ‘When close to him do not attempt to catch hold of him if he shews any sign of struggling or of clutching at you, but await your opportunity of catching him by the hair of his head from behind at the same time throwing yourself on your back.’ Sailors are similarly urged to take the initiative under the headline EXTEMPORE TOURNIQUET: “In the event of an artery being severed anywhere in the arm, at once take off your knife and black silk handkerchief, opening the former and tearing the latter in half.” In the event of a storm, “Always luff to a squall, and ease the sheet.”

Illustrations and descriptions surround Nelson’s Battle of Trafalgar gee-up—of: the Lee-Metford Mark II bolt-action rifle; the Webly pistol Mark IV; exercises for developing sword-fighting proficiency. Life-saving techniques are explained—under the headline SAVING DROWNING PERSONS BY SWIMMING TO THEIR RELIEF: ‘When close to him do not attempt to catch hold of him if he shews any sign of struggling or of clutching at you, but await your opportunity of catching him by the hair of his head from behind at the same time throwing yourself on your back.’ Sailors are similarly urged to take the initiative under the headline EXTEMPORE TOURNIQUET: “In the event of an artery being severed anywhere in the arm, at once take off your knife and black silk handkerchief, opening the former and tearing the latter in half.” In the event of a storm, “Always luff to a squall, and ease the sheet.”

Elsewhere, there are reminders of the importance of obeisance and order—of how to salute (palm of hand aims at shoulder), how to call men to the mess with a bugle, and how to lay out kit for inspection—cholera belts above monkey jacket, for example. The belts were in infact woollen girdles, believed up until at least World War One to protect the itchy wearer from contracing cholera, thought to be caused by a chilling of the abdomen. A monkey jacket was a far more styley thing: wide collar, double breasted, waist length, tapering to a point at the rear.

Elsewhere, there are reminders of the importance of obeisance and order—of how to salute (palm of hand aims at shoulder), how to call men to the mess with a bugle, and how to lay out kit for inspection—cholera belts above monkey jacket, for example. The belts were in infact woollen girdles, believed up until at least World War One to protect the itchy wearer from contracing cholera, thought to be caused by a chilling of the abdomen. A monkey jacket was a far more styley thing: wide collar, double breasted, waist length, tapering to a point at the rear.

Lieutenant-Colonel Carré Fulton came up with his instructional naval handkerchief some time in the 1890s, stamping the cotton rectangle ‘Fulton-Airey Patent Nº 20771'. Fred Airey was Fulton’s fellow creative, a paymaster in the Royal Navy and a talented artist who was commended by the Admiralty for his sketches of the defences of the town of Suakin in the mid-1880s, when the British were attempting to destroy Sudanese forces during the Mahdist War.

Lieutenant-Colonel Carré Fulton came up with his instructional naval handkerchief some time in the 1890s, stamping the cotton rectangle ‘Fulton-Airey Patent Nº 20771'. Fred Airey was Fulton’s fellow creative, a paymaster in the Royal Navy and a talented artist who was commended by the Admiralty for his sketches of the defences of the town of Suakin in the mid-1880s, when the British were attempting to destroy Sudanese forces during the Mahdist War.

Patent Nº 20771 wasn’t Fulton’s first sorte into the hanky business. Nor was he a pioneer; he was probably indebted to Johnny Foreigner for the concept. While a major in the Durham Light Infantry in India in 1885 he released handkerchief patent Nº 10774 onto the market, the target audience being soldiers rather than seamen. The Martini Henry rifle was a dominating motif—the gun had recently contributed to British victories against Malysian nationalists in the state of Perak (1875-76); the Zulu Kingdom in present-day South Africa (1879); and the Emir of Afghanistan near Kandahar (1880). The handkerchief included a definition of ‘a good shot’, one who ‘economises his ammunition and only fires when certain of hitting’. The Homeward Mail (from India, China and the East) reported on Fulton’s ‘novel’ handkerchief in 1886, but commented that ‘similar handkerchiefs are in use in some of the Continental armies’.

Whether Fulton’s military handkerchiefs a.k.a. fighting handkerchiefs were ever issued as part of a British serviceman’s kit is unclear. In a 1893 article entitled “The Marvellous Military Pocket Handkerchief” The South Wales Daily Post reported that, given the War Office (headquarted on Pall Mall, London) had just sanctioned Fulton’s mouchoir, ‘permission to carry these useful articles will now probably be given’, noting that ‘many items are so nicely illustrated that it would be a thousand pities to use it in the manner naturally prompted by a cutting nor’easter’.

Also in 1893, but twelve thousand or so miles away in Wellington, Fulton’s manhood was belittled. The Evening Post quoted ‘an old-fashioned officer’ in the article “Soldiers’ Noses”: ‘The next thing we know the War Office will be issuing umbrellas for every soldier in the army, and a review at Wimbledon will see all the forces manoeuvring under blue gingham. Umbrellas are surely the next thing to official pocket-handkerchiefs. Military life becomes more effeminate every day!’ The Evening Post offered some what-the-heck context as well: ‘Not so very long ago the use of pocket-handkerchiefs by soldiers on duty was not permitted at all...the regulation which required the men to blow their noses, and yet forbade them using handkerchiefs, was irksome to recruits who had been “well brought up”, but was a necessary part of glorious war.’

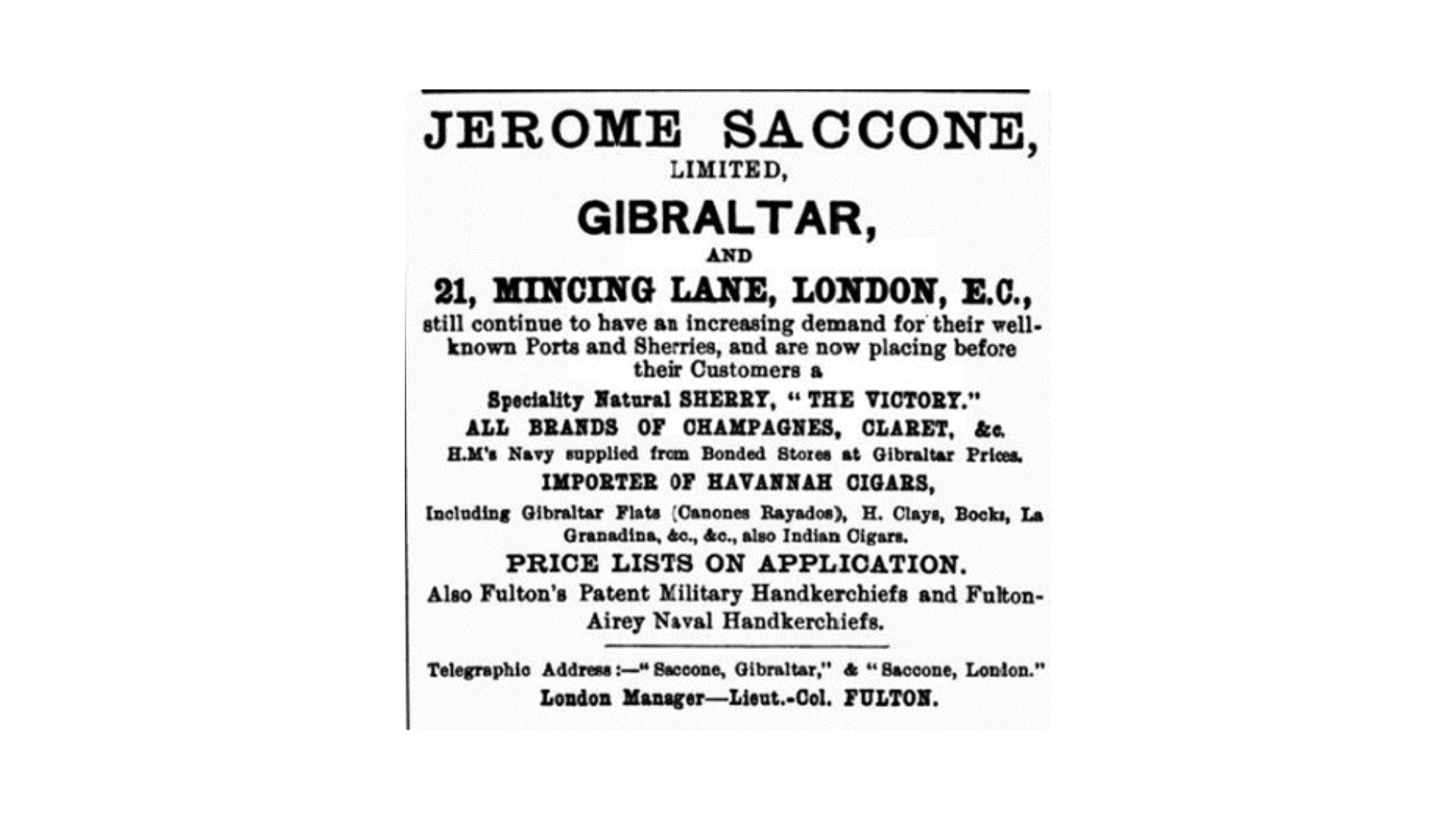

Putting the question of what was included in an official kit aside, it was definitely the case that both servicemen and civilians could buy the hankies. By 1891 Lietuentant-Colonel Fulton had left the Raj behind, retired from the Durham Light Infantry, and was managing the London branch of Jerome Saccone Ltd. Saccone was a terrifically successful wine and spirit merchant (and banker) in the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. He supplied the public but also the warships that regularly called at the highly strategic location—with claret, Champagne, sherry, port, Cuban cigars, and Fulton’s handkerchiefs.

The Army and Navy Gazette, 14 March 1896

The Regiment: An Illustrated Military Journal for Everybody was still offering readers a deal on the hankerchiefs in 1898—5d. (pennies) for an army version sanctioned by the Horse Guards, and 8d. for a naval design. Postage included. The disparity in pricing raised eyebrows at The Army and Navy Gazette: ‘It is a little curious that the Navy handkerchiefs should be just double the price of those for the Army. Is it because Jack is supposed to be just twice as well off as Tommy Atkins?’

*Thanks to Helen Parsons who gifted her father T.C. Windsor’s “Fulton-Airey Patent Nº 20771": to the New Zealand Maritime Museum, in this box: