On the eve of the opening of the exhibition Sentinel at the New Zealand Maritime Museum Matt Rayner* advocates for the very beautiful kawau tikitiki (spotted shag), and argues for an integrated conservation programme on land and sea to protect all our seabirds.

Save Our Shags

Matt Rayner | 8 May 2024

Kawau tikitiki are the glam rockers of the shag world, in breeding season sporting a troubadour crest of white head plumes and turquoise and yellow facial makeup. The endemic species is considered nationally vulnerable, with large but declining populations in the South Island. The situation is far worse in Tīkapa Moana Hauraki Gulf, where the future of a small and genetically unique population is bleak.

The Catastrophic Decline

Historically kawau tikitiki were abundant in Tāmaki Makaurau, with midden deposits suggesting tens of thousands of birds were an important source of kai for Māori. Until 1910 the birds remained widespread, but in 1931 such was the decline in numbers that it became illegal to shoot them—fishers had been enthusiastically taking out the birds in the mistaken belief that they were protecting fish stocks. Kawau tikitiki numbers consequently rose after 1940 and by the 1960s surveys counted over 2000 pairs breeding in the species’ last stronghold of the Firth of Thames. However, by the 1980s colonies were once again in free fall. Today only 250 breeding pairs of this beautiful cormorant remain.

Siloed Conservation Thinking

The case of the kawau tikitiki illustrates how our siloed thinking is not helping seabirds who inhabit two very different worlds—above and below the sea’s surface. In Aotearoa we are globally recognised for our conservation on land: in the last 50 years in Tīkapa Moana alone government agencies and conservationists have cleared at least 16 islands (or island groups) of mammal pests, prevented reinvasion, and restored habitats. This has been great for certain seabird groups that are re-establishing breeding populations, and trending upwards in their old haunts for the first time in centuries.

But here’s the rub. These species are dominated by open ocean and migratory sea fowl—the petrels, shearwaters, diving petrels and storm petrels that use the gulf islands to raise their chicks but depend on its food webs only part time, or in some cases not at all. If we look at our stay-at-home species the situation suddenly looks far more alarming, with catastrophic population declines across a range of seabird taonga, including kawau tikitiki and its shag cousins, as well as terns, gulls, and kororā (little penguin). All these species inhabit the gulf year-round, relying on the productivity of its sparkling waters.

Resorting to Subterfuge

In 2020, concerned for the continued existence of the glam rockers in Tāmaki, Auckland Museum supported by Auckland Council established a programme to boost the breeding population and also to understand the factors impacting the birds at sea. With the species restricted to one main breeding site on Tarahiki Island in the Firth of Thames, we created a fake shaggery on Ōtata Island in the Noises group. This was an attempt to lure birds back to a former breeding site, cleared of pests in the 1990s. At Auckland Museum we scanned and 3D-printed kawau tikitiki specimens held in the collections. Artistic volunteers applied life-like colour. On Ōtata we bolted the dummy shags onto rocks. We sweetened the deal by applying lashings of white paint across the colony to mimic guano, and added a solar-powered sound system which played kawau tikitiki mating calls non-stop.

The ruse should have been irresistible to any young shags looking for a good time and to a limited extent it was—they were visiting within a few months and continue to do so. However, to date the project has failed to establish breeding birds on Ōtata, and from what our research into the maritime lives of the birds is telling us we are beginning to understand why.

You Are What You Eat

At the same time as we busy 3D scanning historic kawau tikitiki specimens at Auckland Museum we were analysing their feathers, as well as those from birds captured in the field. We needed to understand the changes in Tīkapa Moana that might have contributed to the species’ decline. Specifically, we tracked the stable isotope values in feathers dated from 1887-2017 to detect shifts in diet and foraging habitats.

Kawau tikitiki just love fish, however our nitrogen isotope results suggested the birds’ diet has changed over the past century, and they are now eating things that are lower on the food chain: where previously their diet was dominated by fish, they are now eating lower tropic level prey, such as less-nutrient-rich squid. Equally surprising was a carbon isotope result, which indicated the birds’ foraging habitat had moved further offshore between the 1980s and the early 2000s. Coincidentally, this change occurred around the same time that populations began their final decline to today’s numbers.

Gizmos At Sea

All very interesting but we really needed to go out to sea with the birds. In 2021, thanks to a tracking project we commenced doing just this. Birds were caught at their nests on Tarahiki Island and tagged with trackers that log the depth and GPS location for every foraging dive, and upload through the cellphone network.

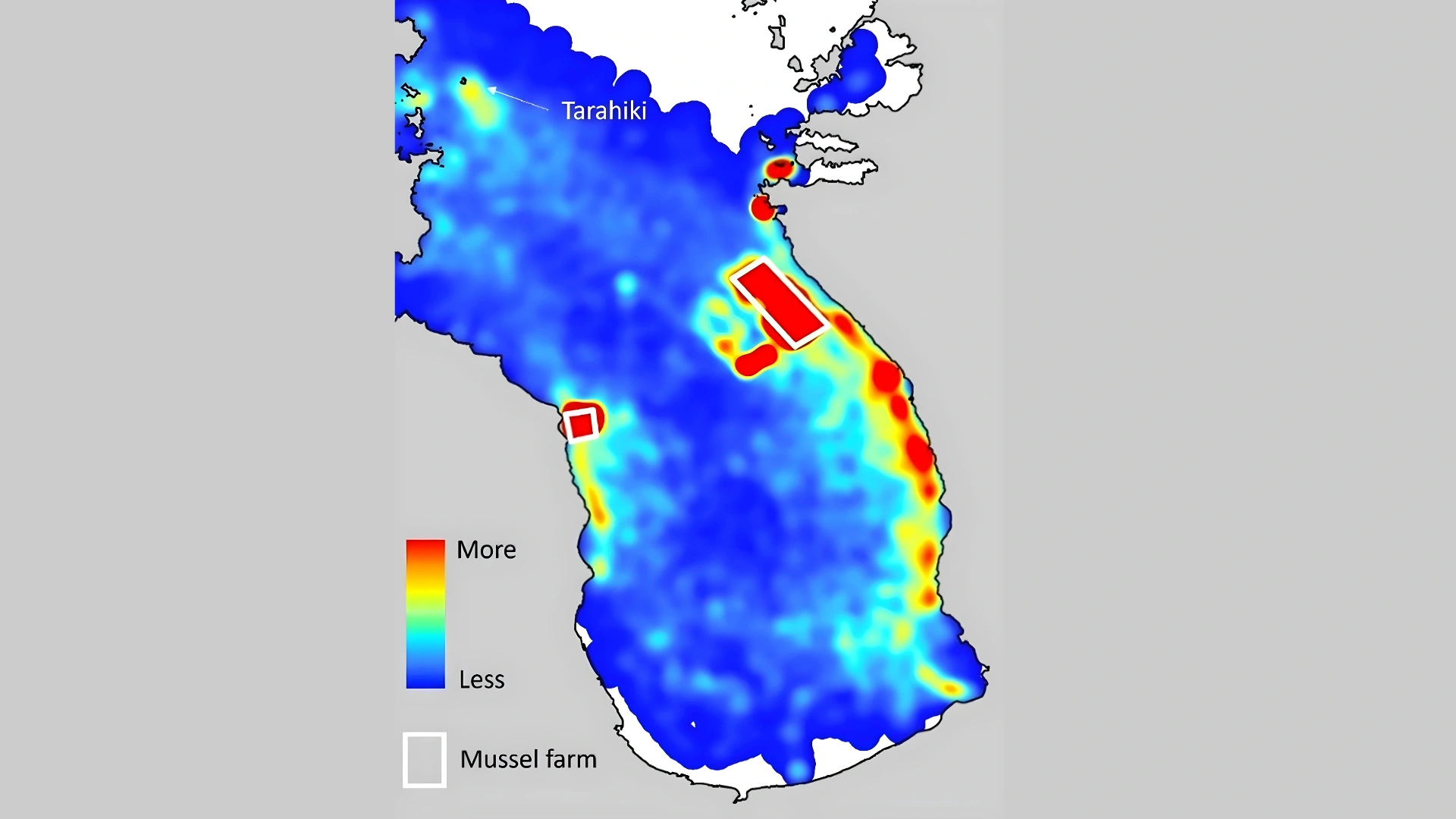

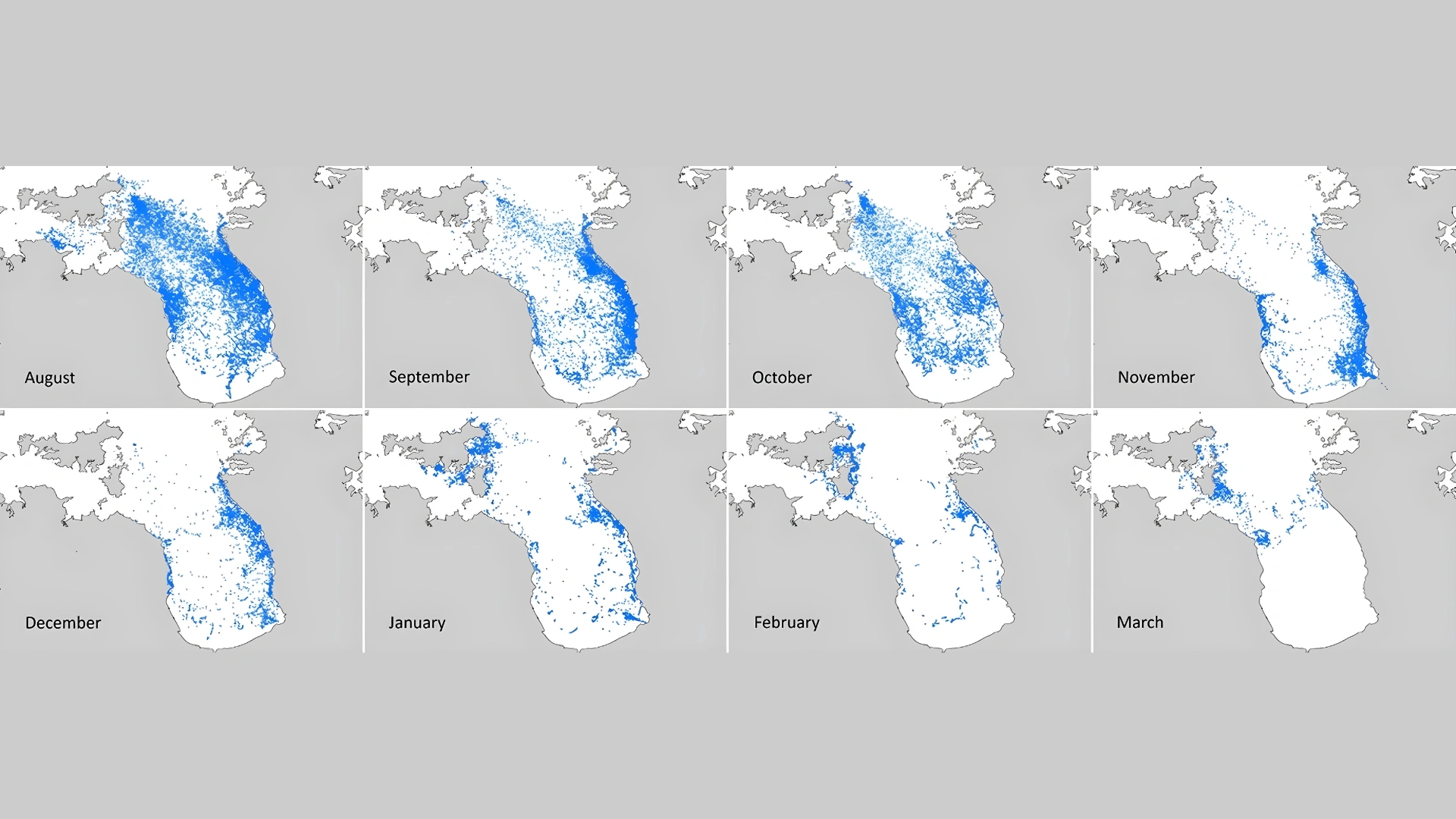

The data provides incredible insight into the challenges kawau tikitiki encounter away from land. Throughout the year tracked birds make extensive use of offshore kūtai (green-lipped mussel) farms in the Firth of Thames, which may explain the change in the birds foraging habitat as revealed by our stable isotope analysis mentioned above. On the farms, birds make shallow dives at the surface, but they also dive more than 20 metres to the seafloor where the kūtai clad lines support a rich marine community, and prey. Recent research shows that fish diversity and abundance is much higher in these marine farms.

Boom and Bust

Tragically, such abundance was once found across much of the Firth of Thames in the form of vast kūtai beds and other benthic structure—such as sponge gardens, cold water corals, and rhodolith beds. Commercial dredging of kūtai beds commenced in the inner Hauraki Gulf in the early twentieth century; by the mid-1960s the fishery had completely collapsed. As is the sad case of so many of our fisheries, we had extracted and destroyed the lot. After over half a century the kūtai beds are yet to recover, prevented from returning by huge amounts of silt and pollutants coming off the land and choking the seafloor.

Hypoxia Explained

Seasonally, tracked kawau tikitiki exploit the southern Firth during late spring and early summer (November-January), and particularly the mouth of the Waihou River where they dive up to 400 times a day in pursuit of prey. However, in February and March birds strikingly abandon the southern Firth, moving into deep water channels surrounding the eastern end of Waiheke, Ponui, Rotoroa and Pakatoa. This shift coincides with a late summer increase in marine productivity, as warm water temperatures collide with vast amounts of nutrient runoff from the Waihou and Piako rivers. This massive boost in phytoplankton and marine algae growth drives down water oxygen levels causing hypoxia, which crushes the entire food chain, impacting all marine life including the fish that kawau tikitiki depend upon.

The Price of Bad Fisheries Management

If a twentieth century kūtai habitat apocalypse and southern Firth of Thames summer dead zone were not enough, our tracking project revealed one more horrific threat to the survival of kawau tikitiki at sea. On Christmas Eve 2023 one of our tagged birds was drowned in a set net about 200 meters off the coast of the Te Puru River mouth North of Thames. It was taken to a boat ramp, its numbered Department of Conservation leg-band ripped off, and then dumped four kilometres inland in a farm ditch. I recovered her body thanks to the still transmitting tag. If this could happen to ten percent of our tagged birds, an extrapolation to a population of 250 breeding pairs makes for a dismal calculation.

If Not Now, When?

Our research of kawau tikitiki shows the pointlessness of current siloed conservation management in Tīkapa Moana where we protect island habitats for breeding seabirds without simultaneously protecting the marine environment on which they rely. It is no wonder birds cannot take advantage of attractive new pest-free breeding habitats, even if sweetened with colourful dummies, fake guano, and sexy sounds. They are too busy trying to survive the destruction of vast areas of former foraging habitat that has forced them to move into deeper waters, the seasonal loss of shallow water fishing grounds due to our nutrification of the water that ends in hypoxia, and the constant threat of an agonising death by drowning as they pursue prey underwater.

With only 250 pairs left, uncertainty lingers over how much longer these cormorants can endure. They serve as a delicate indicator of the complex challenges and issues in the gulf. These can only be addressed with ecosystem-wide restoration and broad societal collaboration. To protect and restore kawau tikitiki populations—and all our precious seabirds—we must get better at simultaneous conservation of land and sea.

This should include protecting and restoring benthic habitats by banning bottom trawling and reducing sediment and nutrient pollution; reducing or eliminating commercial harvest of small prey or forage fish that form the base of the food chain; banning all form of set netting that is an archaic, non-selective and destructive method of fishing; and establishing a network of large marine protected areas where ecosystems can flourish providing food for top predators such as kawau tikitiki. If we hope to preserve these magnificent cormorants for generations, it's crucial that we take action. These birds' survival and well-being are directly linked to the choices we make today.

*Matt Rayner is the Senior Researcher Natural Sciences at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum