By Frances Walsh | September 2024

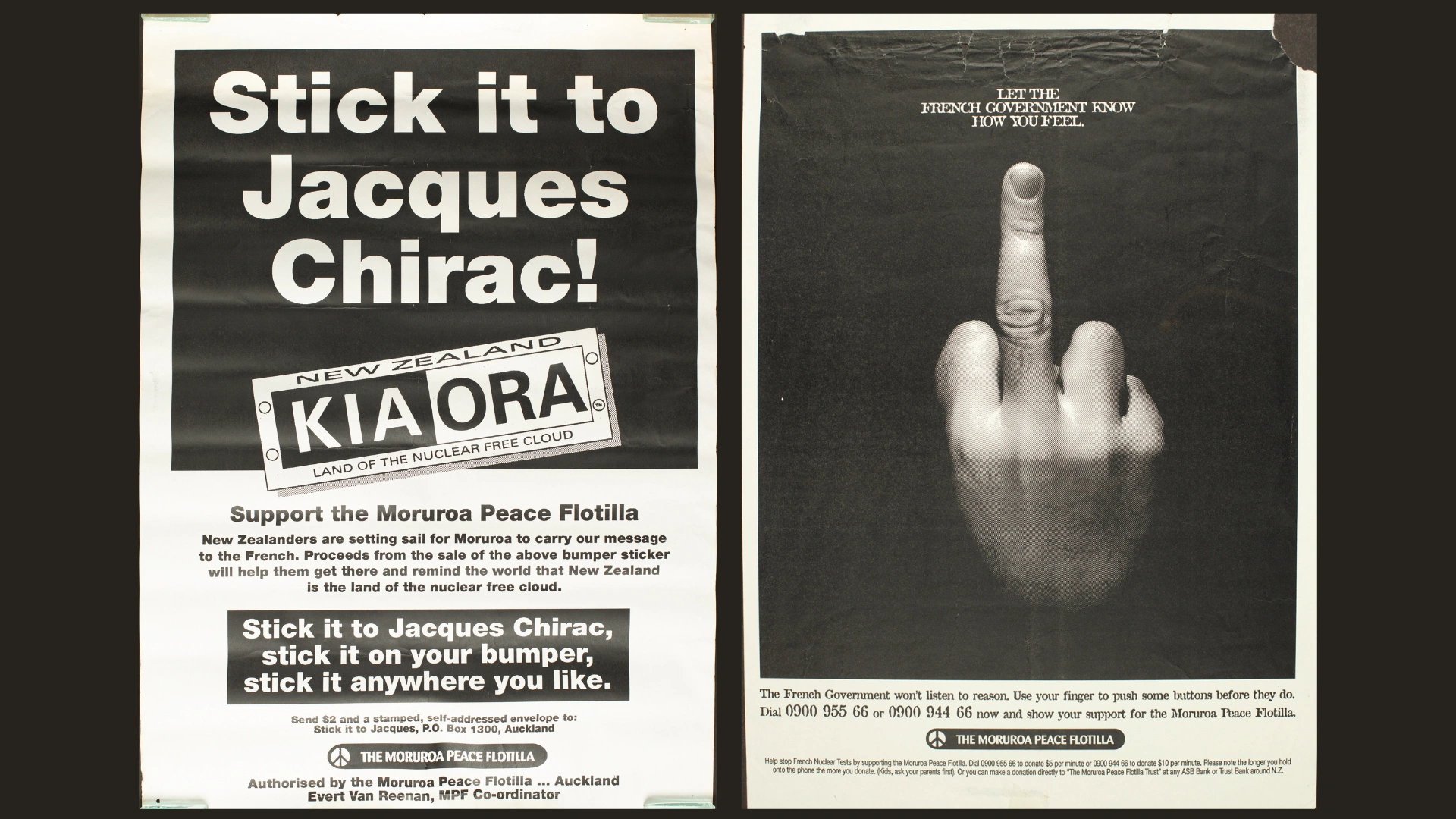

Back in 1995 these two posters gingered up support for a protest flotilla sailing from Aotearoa to Mā’ohi Nui (French Polynesia), to the south-east region of Tuamotu Archipelago. Midway through the year President Jacques Chirac had announced that his country was about to explode more underground atom bombs at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls. The purpose, he and other French mandarins said, to trial a new warhead for submarines; develop warheads with better yield-to-weight ratios; guarantee the safety and viability of France’s nuclear arsenal; secure France’s safety and independence into the twenty-first century.

A Cunning Plan

Fourteen civilian boats sailed up to the testing zone in Mā’ohi Nui to let the French Government know how they felt. Among their number was the tall ship R. Tucker Thompson, from the Bay of Islands; the single-masted steel-hulled yacht Chimera, from the West Coast; and the kauri yacht Vega, a.k.a. Greenpeace III. The strategists behind the flotilla would have made George Smiley proud. Before leaving New Zealand, each boat received a nautical map of the test site around Moruroa and Fangataufa which they could overlay onto a map of inner-city Wellington. When crews needed to rendezvous, rather than exchanging longitude and latitude they referenced, for eg., the corner of Cambridge Terrace and Vivian Street. And the French, who were aggressively monitoring their movements, were clueless.

(L) Overlay map of Tuamotu Archipelago (R) Map of Wellingtons inner city

A Reason to Eat Wattie’s Beanz

The flotilla had enthusiastic support from local luminaries, from both the private and public sectors. Wattie’s, of processed vegetables fame, released a punning poster, ‘They go with the support of Greenpeas.’ As well, the company founded in Hawke’s Bay in 1934 (although by 1995 owned by American company Heinz) donated provisions to the flotilla.

Wattie's poster in support of the peace flotilla, 1995

Prime Minister Jim Bolger also deployed HMNZS Tui to Moruroa—to bear witness and to offer practical assistance, supplying the flotilla with fuel and water, and providing medical services. Tui also transported members of parliament and journalists on various legs. Some voyaged better than others. On route to Rarotonga, Tui’s commanding officer Lieutenant Campbell reported ‘some doubt as to the sea worthiness of the two embarked politicians’.

So Much for Heavy-Weight Pressure

After France had detonated its first bomb in September, Bolger attended the South Pacific Forum—along with leaders from Australia, the Cook Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Republic of Marshall Islands, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Western Samoa. The leaders released a statement expressing ‘extreme outrage at the resumption of French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Forum leaders again demand that France desist from any further tests in the region and call on other countries also to seek to persuade France to cease testing. The forum also note that the painful memories resulting from nuclear testing conducted in the region a half-century ago still haunt many people in the region.’

The spectre of the World War Two atomic bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States, the subsequent death of between 150,000-246,000 people and the ongoing effect of radiation on hibakusha ( ‘survivor of the bomb’) wasn’t sufficiently galvanising, and Chirac detonated another five bombs over the next four months.

Organised Indigenous Resistance

The peace flotilla was part of a decades-old pan-Pacific nuclear disarmament campaign. At Moruroa the flotilla joined another dozen vessels, including the Fijian ferry Kautinoni, the Cook Islands’ vaka moana (voyaging canoe) Te Au o Tonga, Greenpeace’s flagship Rainbow Warrior II and a Tahitian piragua (outrigger canoe). In a coordinated action, when Rainbow Warrior II reached Papeete in late June, around 15,000 Tahitians were in the process of bringing the capital city to a standstill, blocking the streets and roads. At a follow-up protest on the eve of France’s first detonation at Moruroa, lines of marchers snaked for four miles, falling in behind Tahitian pro-independence leader Oscar Temaru and Japan’s finance minister Masayoshi Takemura. ‘Our aim is [to] get our freedom from this colonial power and this nuclear power—they are linked,’ said Temaru. For his part Takemura had brought along photographs of some of the 650,000 hibakusha of the bombing of Hiroshima, with the weapon its designers dubbed “Little Boy”.

Organised resistance to nuclear colonization began as early as the 1950s in the Pacific. In March 1954, the United States’s exploded a 15-megaton thermonuclear bomb (“Castle Bravo”) on Bikini atoll in the Marshall Islands. One thousand times more powerful than the bomb which levelled Hiroshima, it released large quantities of radioactive debris into the atmosphere which carried over 18,000km. The following month 110 Marshallese people petitioned the United Nations over ‘the explosion of lethal weapons within our home islands’, reporting that inhabitants of Rongelab and Utirik atolls [respectively 160km and 490km east of Bikini] were suffering from ‘burns, nausea and falling off of hair from the head’.

On Bikini Atoll

When the United States first began testing nuclear bombs on Bikini in 1946 for ‘the good of mankind and to end all wars’, they persuaded most of the 167 inhabitants to ‘temporarily’ relocate 200km east to the resource-scarce Rongerik atoll. By 1949 they were starving, and were relocated once again, this time to Kili island, 780km southeast of Bikini. It was this geographical and cultural dislocation that Marshall Islanders also referenced in their 1954 petition to the UN: ‘The Marshallese people are not only fearful of the danger to their persons from these deadly weapons…but they are also very concerned for the increasing number of people who are being removed from their land. Land means a great deal to the Marshallese. It means more than just a place where you can plant your food crops and build your houses; or a place where you can bury your dead. It is the very life of the people. Take away their land and their spirits also go.’

A Toxic Legacy

From 1946 to 1996 the Western powers of France, the USA, and the UK conducted more than 315 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests across tens sites in the Pacific islands and the Australian desert. In a recent edition of The Journal of Pacific History, journalist Nic Maclellan refers to the health and environmental devastation caused by the 50 years of nuclear testing, and to the ten sites as ‘sacrifice zones’. He lists Bikini and Enewetak atolls in the Marshall Islands; Monte Bello, Emu Field, and Maralinga in Australia; Kiritimati atoll and Malden island in Kiribati; Johnston atoll in the North Pacific; and Moruroa and Fangataufa in Mā’ohi Nui.

The protest flotilla dispersed and set sail for home early in 1996, after the French government had detonated the last in its series of six bombs—at Fangataufa on 27 January. Thus ended France’s nuclear experimentation in the Pacific. The legacy, however, is ongoing. Published in 2021, a collaborative investigation into France’s atmospheric testing in Mā’ohi Nui between 1966-1974 documents the extent of radioactive fallout and suggests that as many as 110,000 people could claim compensation—a number far greater than officially acknowledged by the French Government. In Moruroa Files, a team from Princeton University, the environmental research collective Interprt, and the newsroom Disclose conclude that ‘In Polynesia, the experience of French nuclear tests is written in the flesh and blood of the inhabitants.’ Cases of leukaemia and lymphoma, as well as cancers of the thyroid, throat and lung, and bone and muscle conditions linked to strontium and caesium poisoning are all prevalent, still.

Images:

Poster: Let the French Government Know How You Feel. NZMM 1995.92.10

Poster: Stick it to Jacques Chirac! NZMM 1995.92.9

Map of the Atolls NZMM 1995.200.3a

Map of Wellington CBD NZMM1995.200.3b